On 23 May, the Home Office published immigration statistics providing the latest figures on those subject to immigration control, for the period up to the end of March 2013.

The statistics demonstrate that immigration abuse is being tackled. The Home Office states that while they continue to encourage the brightest and best migrants, who contribute to the United Kingdom’s economic growth, there is a strong need to tighten current routes into the UK.

Net migration statistics also published by the Office for National Statistics show that net migration has reduced by more than a third since June 2010. According to the Home Office, net migration is now at its lowest level for a decade, falling from 242,000 in the year to September 2011 to 153,000 in the following year.

While it is agreed that net migration is falling, the discussion focuses on how the Home Office is reaching its targets, and the far reaching interpretation of the UK wanting only the brightest and the best.

One of the requirements for those wanting to naturalise as British citizens is that they must be of ‘good character’, the definition of which is subject to caseworkers’ discretion.

GOOD CHARACTER

The topic of ‘good character’ in relation to the acquisition – or, more importantly, the deprivation – of British citizenship has become a hot topic since amendments to the requirement came into force on 13 December 2012. The most notable change was the way in which the Home Office assesses good character in relation to criminal convictions held by applicants for settlement and naturalisation. Immigration and nationality decisions are now exempt from s4 of the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act (ROA) 1974, whereby convictions become spent after the passage of a specified period of time, and instead, will be assessed by caseworkers according to a ‘sentence-based threshold’ as set out in a policy document issued to immigration caseworkers entitled the ‘Nationality Instruction on Good Character’.

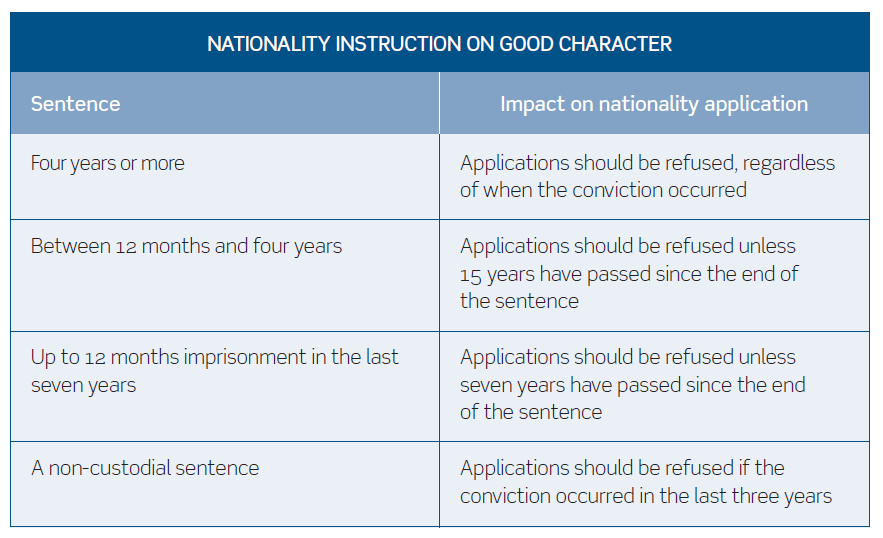

Under the amended good character provisions, applications where a criminal conviction is disclosed will be assessed with reference to the amended set of sentencing limits in the table below.

Although, compared to the ROA 1974 as it currently stands, there appears to be some leniency in the sentence-based thresholds used by caseworkers (for example, the rehabilitation period under the ROA 1974 for certain non-custodial offences is five years, however the sentence-based thresholds require only three years), on the whole they are more severe. In addition, when the new provisions of the ROA 1974 come into force later this year, it is expected that there will be a reduction in the time required for convictions to be considered spent. It is clear that the secretary of state has one direction in mind for British rehabilitated offenders and quite another for those rehabilitated offenders seeking citizenship, who will consequently be punished for their offence for longer than required as a matter of policy, rather than statutory law.

It is worth noting, that the rehabilitation period according to the sentence-based thresholds will conclude at the end of the sentence, rather than at the end of the period of custody. This means that early release from prison will not be taken into account.

Additionally, the Nationality Instruction on Good Character guides caseworkers to adopt a wait-and-see approach to pending criminal convictions, and the naturalisation application will not be determined until a judgment has been handed down by the court.

HOW DOES THIS AFFECT YOU OR YOUR CLIENTS?

Do you ever drive too fast? Have you used your mobile phone while driving? Have you driven without valid insurance? Have you been referred to court for forgetting to pay your television licence? Is your council tax up to date? Are you in debt? Have your teenage children been caught by the police with banned substances? Have you used public transport without paying the correct fare? It is all too easy to fall foul of the Nationality Instruction on Good Character and it is extremely likely that a large number of people will be affected by the non-custodial offence section of the sentence-based threshold.

Although minor convictions resulting in a bind-over, absolute or conditional discharge, admonition, small fine or fixed penalty notice (FPN) will be overlooked, any conviction, even if minor, involving dishonesty, violence, sexual activity, drugs or recklessness (which includes speeding, driving using a mobile phone or driving without tax or insurance) will not normally be disregarded. Minor therefore means extremely minor and anyone who wishes to apply for settlement or naturalisation should bear this in mind. However, the inclusion of the word ‘normally’ in the Nationality Instruction on Good Character leaves caseworkers with considerable discretion and the burden of proof is on the applicant to provide evidence of why the secretary of state should overlook such a minor conviction.

In relation to FPNs used to dispose of minor offences without the need for the recipient to attend court, as there is no admission of guilt involved in the processing of the fine, FPNs do not form part of a person’s criminal record. However, if a FPN is received and challenged by the recipient, but the fine is subsequently upheld by the court, then it would be treated as a conviction and will result in the recipient failing to meet the good character requirement. Although an erosion of civil liberties, clients should therefore be advised to pay any FPN, even if unjustly received rather than risk the failure of any challenge. In the event a FPN was not received in the first instance and the matter is escalated to court without the recipient’s knowledge, as soon as the order is received, the fine should be paid and discretion should be requested in any naturalisation application.

Police cautions are now also assessed against the non-custodial sentencing threshold, although anti-social behaviour orders are not. Only the breach of an anti-social behaviour order is considered a criminal offence.

Any offence or conviction received in the UK or abroad must be disclosed in a naturalisation application, and where an offence took place outside of the UK, it will be assessed in line with the corresponding UK offence and the relevant sentencing threshold will apply.

NO CRIMINAL CONVICTION

Criminal convictions form only one part of the good character assessment and the nationality instructions set out additional guidance to assist caseworkers to determine whether an applicant is of good character. Again, caseworkers are instructed that applicants should not normally be considered of good character if any of the criteria apply and therefore the possibility to exercise discretion exists.

Criminal allegations or suspected criminal activity can also be taken into account where there are reasonable grounds to suspect (for example, it is more likely than not) an applicant has been involved in crime. Therefore, regardless of whether the applicant has been charged or convicted of a crime, the applicant could be deemed not of good character if, taking into account the nature of the information and the reliability of the source of the information provided to the caseworker, there is firm and convincing information to suggest that an applicant is a knowing and active participant in serious crime (for example, drug trafficking). In addition, where there is reliable evidence that the applicant is involved with a gang, caseworkers are instructed that they should consider refusing the application under the good character provisions.

Furthermore, if there are any irregularities in an applicant’s financial affairs – for instance if they have been declared bankrupt, failed to pay taxes for which they are liable or recklessly got into debt – the application could be refused on good character grounds. In the cases of self-employed persons, it is therefore crucial to ensure that all HMRC payments are up to date at the time of submitting an application for naturalisation.

CONCLUSION

While the Nationality Instruction on Good Character gives caseworkers considerable discretion when assessing good character, the standards they are instructed to apply in making such assessments are simultaneously based on ‘a balance of probabilities’ and ‘reasonable grounds’. These different standards create immediate confusion as to the evidential requirements necessary for an applicant to request discretion be applied in relation to the good character requirement.

Furthermore, ‘good character’, in itself, is not defined in statute, and can only be subjectively considered by the caseworker using a policy framework that has not been placed before Parliament in line with the case of R (on the application of Alvi) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2012]. The result is a considerable divergence in the rules for British citizens and the rules for foreign citizens who have made the UK their permanent home.

By Tilly Oyetti, managing associate, and Natalie Loader, trainee solicitor, Magrath LLP.

E-mail: tilly.oyetti@magrath.co.uk; Natalie.loader@magrath.co.uk.