A critical review of corporate structure may result in the conclusion that more can be done with fewer corporate entities. Often our firm is approached by clients that would like to implement a legal entity rationalisation programme aimed at achieving cost efficiency. In the following article, typical issues to be dealt with when liquidating and deregistering a Dutch private limited liability company (besloten vennootschap or BV) entity are discussed.

This article intends to give an insight into the formalities and procedures under Dutch law that have to be considered when the liquidation and/or the winding-up of a Dutch BV is contemplated.

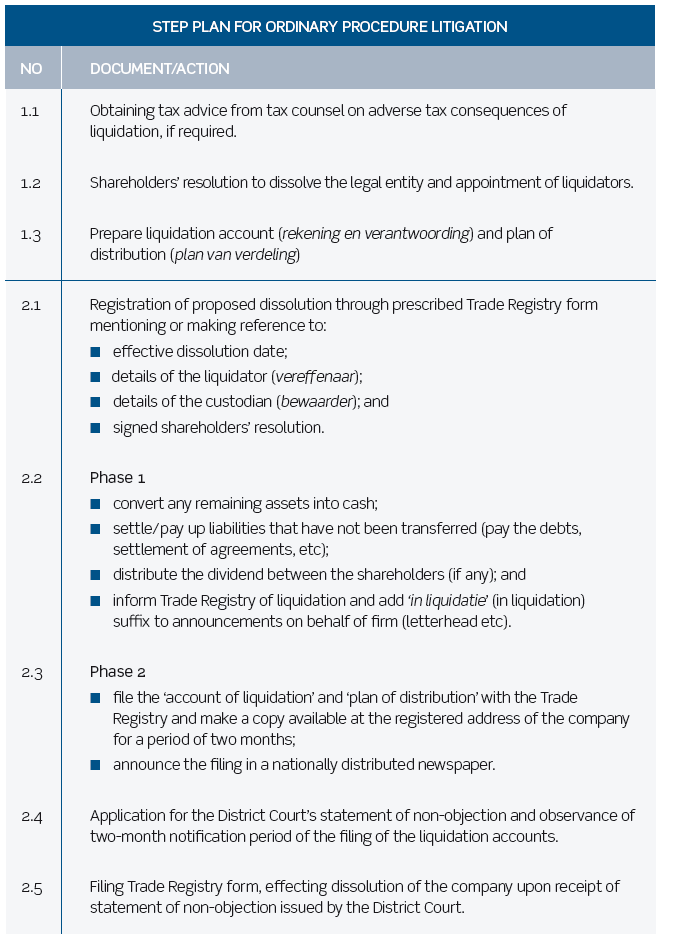

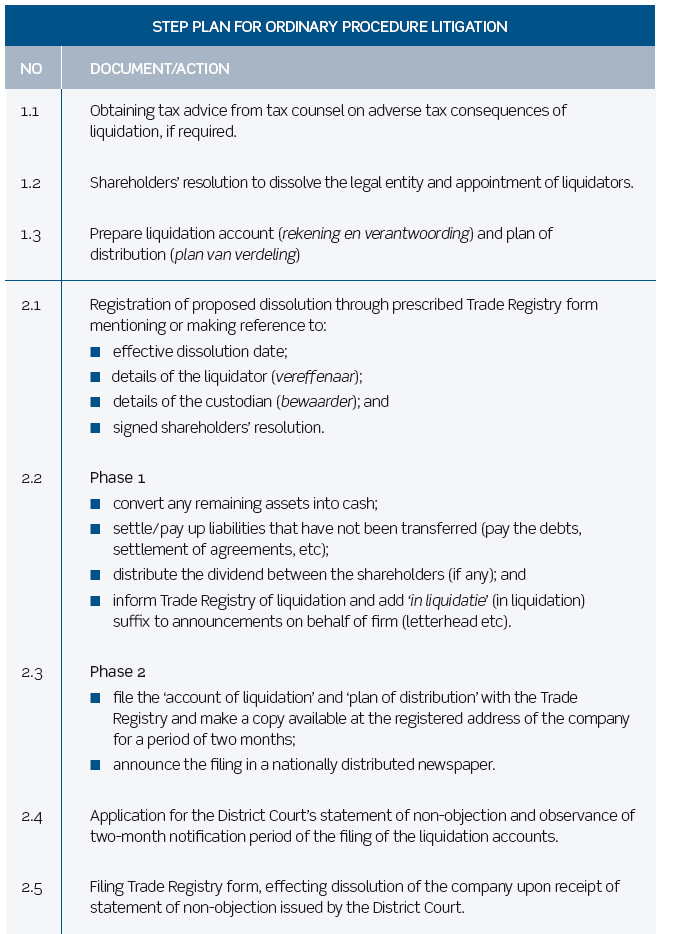

The following subjects are addressed in this memorandum:

- the liquidator (vereffenaar);

- the various procedures that are available for the liquidation of a company; and

- an overview of the steps that need to be taken in order to accomplish a liquidation/winding-up.

This article only relates to the general provisions in title 1 of book 2 of the Dutch Civil Code with regard to BVs, which contains strictly binding provisions for the procedure(s) for winding up (ontbinding) and liquidation (vereffening) of a company.

THE LIQUIDATOR

Dutch law contains requirements concerning the person of the liquidator. In the absence of any provision in the articles of association providing for a liquidator, this task is automatically appointed to the managing directors (bestuurders).

A liquidator has the same rights, duties and liabilities as a managing director, unless this would conflict with the performance of their duties as a liquidator. The articles of association may derogate from this general starting point. If the liquidators establishes that the liabilities will probably exceed the assets they shall in principle be obliged to apply for a bankruptcy order, unless all known creditors, when so requested, concur to a continuation of the voluntary liquidation outside bankruptcy. Most provisions on liquidation set out in this article are not applicable in the event of a bankruptcy and in that event specific bankruptcy legislation applies.

THE PROCEDURES

Under Dutch law, the winding up of a company is usually a prerequisite for liquidation. A legal entity can be wound up, inter alia, by a resolution of the general meeting of shareholders.

There are, essentially, two ways in which a legal entity can be wound up:

- the fast-track procedure; and

- the ordinary procedure.

Under the fast-track procedure, the liquidation in fact precedes the winding up.

THE FAST-TRACK PROCEDURE

The fast-track procedure only applies in cases where the company no longer possesses any known positive assets (baten) at the time of its winding up. In that case, the company automatically ceases to exist once the shareholders’ meeting has adopted the resolution to wind up the company. The basic issue, however, is that unless there are accumulated losses equal to the share capital of the company (in most cases €18,000) it will not be possible to entirely empty the company prior to liquidation, thus necessitating observance of the ordinary procedure.

Notice of winding up

The board of managing directors (bestuur) files notice of the winding up of the company with the Trade Registry. Accordingly, the fast-track procedure is based on the assumption that no liquidation is required. This can also be achieved if the board of managing directors in fact liquidates the remaining assets prior to the winding-up of the legal entity, ie if outstanding debts are paid back and a possible surplus is transferred to the entitled beneficiaries, subject to the applicable tax requirements and obligations.

When the fast-track procedure is followed, liquidation upon winding-up is not required and, as a consequence, the obligation to adopt and file the liquidation accounts and distribution plans no longer applies. However, a document retention period of seven years applies with respect to the books, records and other data.

THE ORDINARY PROCEDURE

If the fast-track procedure is not available, the ordinary procedure has to be followed.If the company is wound up as a result of a resolution of the shareholders’ meeting and liquidation is still required, the company continues to exist. However, only to the extent required for liquidation. In documents and announcements issued by the company, the words ‘inliquidatie’ (in liquidation) must be added as a suffix to its corporate name, so that it is clear to the public that the legal entity is in liquidation and that the scope of the company’s objectives has to be assessed in this light.

Notice of liquidation

The liquidator shall file notice of the liquidation with the Trade Registry. Obligations relating to the company’s accounts remain applicable. Basically, this entails that the obligation to continue the adoption and filing of annual accounts remains applicable.

Liquidation accounts

The liquidator shall prepare liquidation accounts (rekening en verantwoording) containing amounts and composition of the surplus. If there are two or more parties entitled to the surplus, the liquidator shall prepare a plan of distribution (plan van verdeling), stating the grounds for the apportionment. The liquidator shall file the accounts together with the plan for distribution with both the Trade Registry and the registered office of the company, to enable public inspection.

The period during which public inspection should be allowed is two months and the place and duration of the public display has to be announced in a nationally distributed newspaper. Within two months from publication, the accounts and distribution plan can be appealed against (verzet aantekenen) at the District Court (Rechtbank) by creditors and other interested parties.

The liquidator has to file these appeals, as well as decisions on these appeals, in the same manner as the liquidation accounts and distribution plan have to be filed. The liquidator may, where this is justified by the financial situation, distribute the company’s assets to those entitled in advance. However, during the period in which an appeal is possible, the liquidator may not do so without prior authorisation of the District Court.

The liquidator shall use the company’s assets for the satisfaction of the creditors’ claims. Any surplus assets of the company subject to liquidation shall be transferred to the shareholders. If the company’s assets include items other than cash and they are not designated for a specific disposal, the liquidator may, inter alia, sell them and distribute the (net) proceeds of the sale among the shareholders. Cash funds that have not been claimed by those entitled within six months after payment was due, must be deposited into a fund for payment by the liquidator.

End of the liquidation

The liquidation ends when the liquidator is not aware of any further existing assets of the company. After expiry of the two-month period following the announcement in a nationally distributed newspaper, a statement of non-objection is to be obtained from the District Court by way of confirmation that no objections have been raised against the liquidation. Upon completion of liquidation, the company shall cease to exist and the liquidator shall file a notice with the Trade Registry, where the particulars registered in respect of the company will be maintained for ten years.

After the company has been wound up, a document retention period of seven years applies with respect to the books, records and other data. The custodian (bewaarder) shall be the party designated in the articles of association or by a resolution of the general meeting of shareholders. In case there is no custodian and the liquidator is not able or willing to keep these documents, a custodian shall be appointed by the District Court. Within eight days after their custody obligation takes effect, the custodians must notify the relevant Trade Registries of their name and address. The District Court may, upon application, give authorisation for inspection of the books, records and other data to any person proving a reasonable interest in such inspection. This includes former members or shareholders of the company, holders of depositary receipts for shares (certificaathouders) or assignees of such persons.

by Aravind Ramanna and Tim Carapiet, lawyers in M&A and capital markets,

E-mail:aravind.ramanna@boekeldeneree.com; tim.carapiet@boekeldeneree.com

The Dutch Civil Code

The Code contains a far-reaching provision: if, after the company has ceased to exist, another creditor or party entitled to the surplus appears or the existence of an asset is ascertained, the District Court may, on the application of any interested party, reopen the liquidation and, if necessary, appoint a liquidator. From specific case law it can be concluded that a liquidated company can be a party to legal proceedings without the prior reopening of the liquidation.

As a result, the company could be revived solely for the purpose of reopened liquidation. Note that in this case the liquidator may demand repayment from the former shareholders or other persons entitled of whatever amount they received in excess of the amount to which they would have been entitled under the liquidation, had all parties entitled to the surplus been known at that time.