Following the recent High Court decision in Tamiz v Google Inc [2012], which closely followed the decision by HHJ Parkes QC in Davison v Habeeb [2011] just two months earlier involving the same defendant, you may have been mistaken for thinking that the law was for once attempting to move at the pace of technology. However, despite Mr Justice Eady stating in Tamiz that he was ‘striving to achieve consistency in the court’s decision making’, he appears to have come to a very different conclusion by holding that Google (as host of Blogger.com) was not (rather than arguably could be) a publisher at common law, regardless of notification.

Although Eady and Parkes agreed that the tool of analogy was a useful one in helping apply traditional common law principles to new technologies, Parkes claimed Blogger.com was like a gigantic noticeboard over which Google had control, while Eady claimed that the posting of defamatory statements on Blogger.com was similar to graffiti being sprayed on the wall of a helpless wall owner. While the analogies may be visually clear, the resulting legal position is not. So, was the decision in Tamiz right, what effect does all this have on libel claimants defamed online and what are their options going forward?

Challenges to managing online reputation

Managing the reputation of corporations and individuals on the internet can be challenging. If defamatory statements are posted on a website by an individual, identification of that individual is often hard to establish within a short space of time. The individual will have probably registered on the site using a fake name thus making themselves anonymous and even if a real name is used, contact details will usually only be obtainable from the site themselves who will not release them unless compelled by a court order, which takes time. It should also not be forgotten that obtaining an interim injunction in defamation proceedings is almost impossible1 and unless the defamed party can persuade the author, online operator or host to take down the offending words, they could remain there until a successful judgment is obtained at trial. Therefore, the ability of the claimant to pursue a host as a common law publisher and compel them to take down (rather than chasing anonymous bloggers) will often allow a claimant to obtain a quicker result.

Establishing liability for the publication of defamatorymaterial online

Subject to overcoming the hurdles of substantial publication2 and seriousness3, a claimant must overcome any possible defence available to a publisher under s1 of the Defamation Act (DA) 19964. If successful, the publisher will be liable prima facie. However, a claimant must provide an online publisher (such as a host) with ‘actual knowledge’ of an unlawful activity to overcome the hosting defence under Regulation 19 of the E-Commerce Regulations 20025. If the higher evidential burden of ‘actual knowledge’6 is discharged, the only course of action available to the host to avoid liability is to remove the unlawful content. An author’s internet service provider (ISP) that plays no more than a passive role in facilitating is not a publisher as it expends no mental element in the process of publication and therefore assumes no responsibility for it7. Neither is a search engine8.

In Davison, Parkes stated that Google, as host of Blogger.com, was arguably a publisher under the common law and that liability would follow notification, although Google ultimately defended the case successfully utilising a Regulation 19 defence. Had ‘actual knowledge’ been provided, Google Inc would have been liable as a publisher but, despite the very similar facts in Tamiz, the opposite decision was made with regards to whether Google was a common law publisher.

Tamiz v Google: the decision

The case involved defamatory postings made anonymously on Google’s Blogger.com against Payam Tamiz (one-time Tory election candidate). He complained to Google who, after some considerable delay, passed Mr Tamiz’s complaint onto the anonymous blogger who voluntarily removed the offending material. Mr Tamiz issued proceedings against Google (not the author) claiming damages in respect of defamatory postings.

Google Inc applied to set aside an order of the court granting permission for the claimant to serve the claim form outside the jurisdiction (California) on the basis that there was no arguable case as Google had no control over any of the posted defamatory content and was therefore not a publisher. Mr Justice Eady agreed that Google Inc was not liable at common law as a publisher stating:

‘It seems to me to be a significant factor in the evidence before me that Google Inc is not required to take any positive step, technically, in the process of continuing the accessibility of the offending material, whether it has been notified of a complainant’s objection or not… As I understand the evidence its role, as a platform provider, is a purely passive one. The situation would thus be closely analogous to that described in Bunt v Tilley and thus, in striving to achieve consistency in the court’s decision making, I would rule that Google Inc is not liable at common law as a publisher’.

Notification did not automatically convert Google’s status to a publisher and Google’s technical ability to remove material did not make it an author or authoriser. Nor did accepting responsibility to notify the bloggers involved. Eady also stated that in any event, Google would have had a defence under s1 Defamation Act 1996 and Regulation 199. Accordingly, the High Court declined jurisdiction on substantive grounds and the original order was set aside.

Was this consistent decision making?

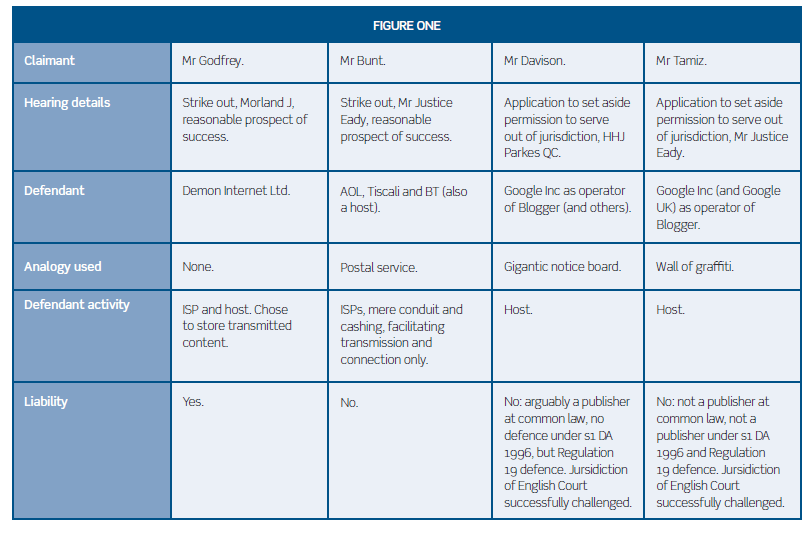

(See figure one for an overview of the important decisions)

Eady claimed in Tamiz that he was guided by the need to be consistent. Yet it is well established that such cases are fact sensitive. It is crucial to look at what the defendant actually does in the chain of communication, the mental element involved and the extent of the defendant’s knowing involvement in the process of publication to establish responsibility for it, see Bunt v Tiley. Yet, despite Davison, Eady claimed that Google’s role in hosting Blogger.com was analogous to that in Bunt and that in order to be consistent with this previous authority, Google were not liable in the same way as the ISPs in Bunt.

However, such reasoning seems inconsistent. Why did Eady choose to use an authority from 2006 concerning ISPs rather than rely on Davison decided two months previously on similar facts as his basis for consistent decision making? Davison involved the same defendant in the same capacity and it was acknowledged in that judgment that Google did not play a passive role and ultimately had control over the content posted otherwise its terms and conditions policy would have been a sham. Blogger.com also has the ability to remove words, which Parkes stated was ‘highly relevant’. Even Eady himself acknowledged in Metropolitan Schools10 that a hosting website may be liable on the basis of acquiescence if, having the power to remove objectionable material, they do not remove it following notification.

Tamiz also seems inconsistent as it appears to overrule Godfrey v Demon Internet [1999] even though the similarities between both cases could not be clearer. In Godfrey, Demon hosted a Usenet newsgroup, received and chose to store postings made on Usenet and transmitted them upon request from storage. Demon could also obliterate postings stored. Blogger.com is arguably the same, rather than a mere facilitator playing a passive role, in Bunt.

So what about Tamiz’s consistency with Bunt?

Taking all the similarities between Tamiz, Davison and Godfrey into account, to base the decision made in Tamiz on Bunt seems flawed for a number of reasons:

- The facts in Bunt were totally different to Tamiz and involved three ISPs. Google is not an ISP, which Eady compared in Bunt to a telephone service or other passive medium. An ISP is a facilitator providing access and is very different to a host like Google who create and operate platforms and store content, which it can remove. Such differences were acknowledged throughout Eady’s judgment in Bunt in the evidence of Nigel Hearth (director of technical operations for AOL)11, by Eady himself12 and in relation to BT’s dual role as ISP and host13.

- It was not pleaded in Bunt that any of the ISPs hosted the website on which the defamatory postings were made but that the ISPs provided the services to enable the author to connect to the internet, did not knowingly participate in publication and only played passive roles in facilitating access.

Other merits of the Tamiz decision

While it seems that the decision in Tamiz is arguably not consistent with either Davison or Bunt, in further support of his decision in Tamiz, Eady stated that one should guard against imposing legal liability in restraint of Article 1014, where it was unnecessary or disproportionate to do so, agreeing with Google’s argument that, practically, it could not investigate every complaint brought to its attention. However, this fails to take into account a number of issues.

- Although Google says it cannot adjudicate or investigate the veracity of postings and that removing material is impractical without a court order, this argument is contrary to the affect of the E-Commerce Regulations as, once a host has actual knowledge of unlawful material via notice, a host is compelled to remove the unlawful material to avoid damages regardless of any intervention by the court.

- Although it was acknowledged in both decisions that it would be impractical for Google to monitor postings, Parkes in Davison stated that Google would only become a publisher after being provided with actual knowledge. It would then be consenting to and participating in publication unless it removed the material. Therefore, no monitoring by Google is actually involved as the claimant simply directs them to the unlawful material via notification. It cannot be right that a host cannot assume responsibility at this point, taking into account the contractual relationship with the author via its content policy and its ability to delete material. The recent comments by the Joint Committee on Privacy and Injunctions that Google should take steps to ensure their websites are not used to breach the law and the description of their objections to doing so as ‘unconvincing’ should be noted15.

- There is no presumption in favour of Article 1016 and Eady failed to take into account the right of Mr Tamiz to protect his reputation under Article 8. It would have been more proportionate a balance between these two competing rights for Google to have been held a publisher under common law and for notification in the form of ‘actual knowledge’ to be the ultimate touchstone for liability rather than preclude Mr Tamiz from any practical remedy. Even if a claimant overcomes the significant protection afforded under Regulation 19, the host defendant can still avoid liability by removing the unlawful material. The words of Lord Hobhouse in Reynolds v Times Newspapers Ltd & ors [1999]17 should also be remembered in that ‘there is no human right to disseminate information that is not true’, making Article 10 considerations weaker where false and defamatory allegations are concerned. Mr Justice Eady has affirmed these views very recently, stating why it is in the public interest for those who knowingly publish false information on the internet to be stopped.18

Implications of the Tamiz decision

It now seems that the claimant’s proper course of action in law will be to pursue the author in many cases. However, although the existence of a cause of action against the author (rather than Google) meant that Mr Tamiz still had access to justice, as Eady admitted, tracking down the author is not easy if they are anonymous. This practical problem juxtaposed with the speed at which defamatory content can be accessed and disseminated via the internet by anyone anywhere in the world, makes the decision unhelpful at the very least. No doubt, other platform hosts will argue that they fall under the same category as Google. Could Tamiz mean that every host is now exempt?

The immediate way forward

Against this back drop of uncertainty, the worldwide popularity of social media and the growing abuse of the internet at the hands of the anonymous, what are the alternatives?

- Appeal the decision: it is understood that, at the time of writing, the decisions in Davison and Tamiz are subject to appeal.

- Distinguish the facts: it may be possible for practitioners to distinguish the two first instance decisions of Tamiz and Davison based on the actions being taken by hosts in comparison, for example, where a host does more than store content and is also an administrator. Tamiz also involved posted comments while Davison involved a posted article.

- New methods: new hi-tech ways to identify and pursue individuals exist, such as third-party disclosure orders (by-passing the need to obtain a Norwich Pharmacal order) and alternative methods of service, such as via Twitter (Blaney’s Blarney orders), Facebook, mobile numbers (Bingle orders) and IP addresses in defeating BitTorrents (see AMP v Persons Unknown [2011]).

- Technical approaches to reputation risk strategy: search engine optimisation allows corporations and individuals to create and link their online metadata with new, high-ranking content in an organic and ethical way to improve search engine results and de-rank and displace unwanted results and offending material.

- Pre-emptive analytical approaches to reputation risk strategy: this involves understanding potential online risks and taking steps to minimise them before they occur. There are tools to help organisations and individuals understand their reputation position. A full reputational health check is an invaluable exercise for devising a robust reputational risk framework.

Conclusion

While the government intends to deal with responsibility for online publication, anonymity and the role of hosts in the draft Defamation Bill, it is clear that, in the digital age, the effective management of online reputations will involve a combination of both legal and technical measures. Still, whatever the future holds, let’s hope that our decision makers have their Google Maps the right way up!

By Michael Yates, solicitor, Schillings.

E-mail: michael.yates@schillings.co.uk.

Notes

- See Bonnard v Perryman [1891] as reaffirmed by Greene v Associated Newspapers Ltd & anor [2004].

- Jameel (Yousef) v Dow Jones & Co Inc [2005]: a claimant must establish a real, substantial tort, which means showing not just that the allegations have been read, but also that there are some grounds for believing that it has been given a measure of credence by readers and thus been liable to affect the claimant’s reputation in their eyes. The fact of publication cannot be inferred solely by reason that the allegations are accessible on the internet.

- Smith v ADVFN Plc & ors(No 2) [2008], comments on blogging sites must not be mere vulgar abuse.

- Section 1(1) Defamation Act 1996 states as follows: ‘1(1) In defamation proceedings a person has a defence if he shows that (a) he was not the author, editor or publisher of the statement complained of (b) he took reasonable care in relation to its publication, and (c) he did not know, and had no reason to believe, that what he did caused or contributed to the publication of a defamatory statement.’ Also see ss(2)-(6).

- The Electronic Commerce (EC Directive) Regulations 2002, SI 2002/2013, Regulation 19 (Hosting Defence) states; ‘(19) Where an information society service is provided which consists of the storage of information provided by a recipient of the service, the service provider (if he otherwise would) shall not be liable for damages or for any other pecuniary remedy or for any criminal sanction as a result of that storage where: (a) the service provider: (i) does not have actual knowledge of unlawful activity or information and, where a claim for damages is made, is not aware of facts or circumstances from which it would have been apparent to the service provider that the activity or information was unlawful; or (ii) upon obtaining such knowledge or awareness, acts expeditiously to remove or to disable access to the information, and (b) the recipient of the service was not acting under the authority or the control of the service provider.’

- Regulation 22 of the E-Commerce Directive is the starting point regarding notice for the purposes of actual knowledge. The courts have built upon this and acknowledge that mere notification of a defamatory statement does not amount to actual knowledge of an unlawful activity as a defamatory statement is not necessarily ‘unlawful’ (see Kaschke v Gray [2010], Davison and now Tamiz). A claimant must also provide the strengths and weaknesses of available defences involved (Bunt v Tilley & ors [2006]). Any effort by the defendant to substantiate their defamatory allegations forcing the host into the role of an adjudicator will make it less likely that they have been provided with actual knowledge that the allegations are ‘unlawful’ (Davison). Outlandishness of the allegations cannot be a supporting factor of unlawfulness as an allegation’s outlandishness would be equally apparent to those reading it (Kaschke). Notification by the claimant is only one factor that a national court must consider given that notifications may turn out to be insufficiently precise or inadequately substantiated, see the Grand Chamber’s decision in L’Oreal SA & ors v eBay International AG & ors [2011].

- Bunt v Tilley & ors [2006].

- Metropolitan International Schools Ltd v (1) Designtechnica Corporation (2) Google UK Ltd (3) Google Inc [2009]

- Google did not have ‘actual knowledge’ because of the absence of any details from the claimant as to the unlawful nature of the postings (including no explanation as to the extent of inaccuracy or the inadequacy of any defence). Eady commented that a provider such a Google is not required to take a claimant’s protestations at face value.

- See paragraph 54 of Mr Eady’s judgment.

- Nigel Hearth at paragraph 52(5) stated that content from a page hosted and permanently stored by Google sits on computers controlled by Google (as opposed to an ISP like AOL who provide a connection as a mere conduit or store temporarily the content of the host via caching).

- Eady at paragraph 8 of his judgment stated that ‘Usenet service is hosted by others, who are not parties to these proceedings, such as Google’. Therefore, even he stated that a host like Google had nothing to do with his decision in Bunt.

- BT were considered again at the end of the judgment as they hosted the Usenet newsgroups on their servers and were treated differently to the other ISPs. BT therefore relied on Regulation 19 rather than Regulations 17 or 18 of the E-Commerce Directive 2002. It is therefore unclear whether Eady’s general findings at paragraph 36 of the judgment apply to BT in this capacity.

- The right to freedom of expression under Article 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights.

- Privacy and Injunctions Report 2012, paragraph 115

- Re S (A Child) (CA) [2003].

- Reynolds v Times Newspapers Ltd & ors [1999], judgment of Lord Hobhouse who stated: ‘… it is important always to remember that it is the communication of information not misinformation which is the subject of this liberty. There is no human right to disseminate information that is not true. No public interest is served by publishing or communicating misinformation. The working of a democratic society depends on the members of that society being informed not misinformed’.

- Law Society & ors v Kordowski [2011], see paragraph 175 onwards.