The London office of peer-to-peer lender Funding Circle is exactly what you would expect from one of the UK’s largest and most high-profile fintech businesses.

Julie Smyth: BAE Systems Air

‘My husband has virtually no understanding of what I do,’ admits BAE Systems Air chief counsel Julie Smyth. ‘He thinks I sit in meetings all day.’ Continue reading “Julie Smyth: BAE Systems Air”

No great advantage

Alex Speirs: Now less than a year out from the UK’s scheduled withdrawal from the EU, how would you characterise the current state of negotiations?

Dominic Grieve: They’re not going well at all. We are not talking the same language. The UK is seeking a bespoke deal recognising our past membership of the EU, our desire to maintain very close links with the EU in a wide range of fields, to have as near frictionless as possible trade in goods and services, and to participate in a vast range of EU peripheral activities. But we want freedom to operate our own immigration policy, not have freedom of movement, the ability to do third-country trade agreements and the ability to deregulate or change the regulatory framework in areas.

It’s what our EU partners characterise as ‘having your cake and eating it’ – and that is, plainly, what we are asking for. Although the prime minister has altered her position in the knowledge that we might not get everything we want, each time she’s made a major speech, each speech has essentially been that same message. And the response has consistently been coming back from the EU Parliament that they won’t give it to us. This is very predictable. The UK Government’s view is that, at some point, the EU will moderate its position, just as the EU thinks that at some point we will change our position. It’s difficult to see how the positions of both parties will be reconciled.

AS: Why has the UK taken this approach to negotiations?

DG: It shows the reasons people voted to leave and why people have accepted the vote to leave are very complex and often incompatible. You’ve got, within UK society, deeply polarised viewpoints, plus the fact that those who voted remain have been utterly unpersuaded that there is any benefit to leaving.

In the middle of that, you have a government led by a prime minister who voted to remain. She may have been lukewarm about the EU, but she voted remain because she could see leaving was going to be extremely risky, complicated and potentially damaging to the UK economy. But in trying to minimise those risks, she is angering the purest leavers for whom the three things of no freedom of movement, free trade deals and no European Court of Justice [ECJ] are absolutely paramount.

That’s why, having kicked the can down the road for two years, we are now coming to a crisis – time is running out. Otherwise, we careen out of the EU with no deal and then it’s not at all clear what would happen.

AS: Is it more likely than not the UK concludes negotiations with no deal?

DG: It would be very surprising to end up with no deal at all. If we are going to end up with no deal on anything, unable to reach an agreement on the terms of withdrawal, let alone a future framework, we are heading for a potentially catastrophic situation. Catastrophic for us, but pretty catastrophic for the EU, because essentially the ability to trade in goods and services would come to an end. I can’t believe that’s in anyone’s interest, which is why a complete no deal is quite improbable.

If we are leaving without any deal for our future relationships and trade terms, there is a very serious crisis brewing – bad for our continental partners in the EU, but very bad for us. I cannot see a government surviving that. You’d be talking about a general election, a referendum or even extending the article 50 process.

AS: The EU Withdrawal Bill has been a point of contention of late – and an issue which you have been at the centre of. Why has there been such controversy around its negotiation?

DG: It’s important to understand that the EU Withdrawal Bill is not about the terms of our withdrawal from the EU. It is about putting in place a safety net to ensure that on the day we leave the EU, or at least the day we come out of transition, we have a system that will enable us to prevent a legal void when EU laws cease to apply. In theory, it ought not to have been particularly controversial. But it had a number of controversial elements.

Firstly, the way in which you carry out retention of EU law. There were issues around the extent to which the Government was trying to use Henry VIII powers – the power to change primary legislation by statutory instrument. The Government’s argument, which was reasonable, was that because of the timeframe, you would not be able to carry this out without the Government having extensive powers to legislate via statutory instrument. So one big area of debate was: how should those powers be controlled? We introduced amendments that dealt with sifting committees and increased parliamentary scrutiny, and debated how those powers should be restricted.

Secondly, although the Government had been talking about retaining EU law until such time where it had decided what to do with it, there were some elements they chose not to retain at all. That raised important issues, because there are areas of law that have developed in the UK over the past 50 years, like equality law, that are entirely subject to the general principles of EU law and a Brexit would leave these areas entirely unprotected.

The final controversial element was less expected. It gave the Government power to use statutory instruments to implement change to our legislative framework, even before Parliament had approved our withdrawal agreement terms. I considered there was a fundamental objection to doing that. This dovetailed into a wider issue about controlling the process of leaving and particularly the issue about Parliament having a meaningful vote on any deal, and what should happen in the event of no deal, which would be, frankly, a major national crisis.

I wanted to put in place a system to deal with no deal that was predictable. But if we end up with no deal, the idea Parliament can be excluded is fanciful.

Now, on a meaningful vote on any deal, the Government conceded at an early stage that Parliament would have to have such a vote. They’ve now enshrined it in statute after quite a lot of pushing from the Lords and the Commons.

AS: When negotiating amendments to the EU Withdrawal Bill, what were the concerns you were seeking to address?

DG: I was concerned with the oddity that on the one hand, leaving the EU was supposed to be about recovery of Parliamentary sovereignty, while on the other, we were being asked with the EU Withdrawal Bill to hand vast chunks of sovereignty to the executive. That’s always what happens in a political crisis – the centre takes power to try to control what’s going on. I wanted to make sure this bill was properly scrutinised. Nobody in the House of Commons wanted to prevent this bill going through, because it’s clearly vital. If we don’t have it, we’re still going to leave the EU next year. It’s just that when we leave the EU on 30 March, people would wake up to discover that, effectively, vast areas of law had disappeared. We would be living in a lawless environment.

The process is now in place. I would have preferred the amendment I put forward two weeks ago, but then voted against because it was endangering the Government’s survival, which shows the fragility of the environment in which the Government is operating. I wanted to try to put in place a system to deal with no deal that was more predictable. But, it’s a slightly peripheral issue – if we do end up with no deal, the idea Parliament can be excluded from the process of considering this is fanciful.

AS: There are obvious issues on the statutory law front, which we’ve discussed. Is there any sense of what’s going to happen to common law decisions based on the UK being part of the EU?

DG: We are facing a very major change. One of the issues that was highlighted during the passage of the bill was that there had been concerns from senior members of the judiciary about uncertainty with regards to how they were supposed to interpret retained EU law.

The judges were troubled and some expressed concerns, saying: ‘It’s all very well, but we will be the ultimate arbiters of the retained EU law, not the ECJ.’ Also: ‘To what extent is Parliament saying that we should be mirroring the ECJ, or should we be doing our own thing?’

But there is an ambivalence around the whole process of leaving the EU, because on one hand, the Government is trying to uncouple us from the jurisdiction of the ECJ. On the other, there are repeated suggestions that once we are out, we are still going to mirror virtually the entire canon of EU regulatory law, to re-facilitate trade with the EU.

AS: Is there any opportunity for Britain in Brexit?

DG: I can’t say there cannot be some silver lining. If you believe the EU is dysfunctional and may be having problems that could undermine or destroy it in the medium term unless it changes, then Brexit offers greater freedom of national action – if we can get it in terms of our exit deal. It’s worth noting that most of the Government’s effort at the moment seems to be devoted to trying to replicate trade deals we are going to lose. But I don’t think any of those trade deals will replace the loss of trade we are going to experience with our EU partners, who are our closest neighbours and with whom we do most of our business. I don’t really see any great advantage.

The other advantage one hears is that it would give the UK the opportunity to break free of the shackles of EU regulation and deregulate, somehow turning ourselves into the Singapore of the north-east Atlantic. But there are two problems with that: one is that, for our European trade, we are going to continue to have to meet EU norms; and the second is that we could deregulate our services more, so that we would have the opportunity to operate in a much leaner, meaner environment. The trouble is that there doesn’t seem to be much evidence this is what the British electorate wants. Although they talk about EU regulation in a critical way, if asked to identify EU regulation they want to get rid of, they are incapable of doing so.

AS: What impact will Brexit have on Europe in the long term?

DG: Europe has a lot of problems. You only have to see what’s going on in countries like Italy, Hungary, or indeed the phenomena in big players like Germany and France, to see the EU is in crisis. That crisis comes from two things.

The first is that the 2008 economic crash had a profound effect on public confidence as to what the EU’s offer was. The EU’s capacity to get out of that has proven to take much longer than they had wished and the euro, because it skews the economies of some of Europe, means they have not yet succeeded in finding a framework for bringing everybody together. It doesn’t appear to work to the advantage of some countries.

Then you’ve got migration, which is becoming a huge issue that politicians have failed to grapple with. Angela Merkel’s decision to open the borders of Germany to over a million refugees – while I can understand from a moral standpoint – was, as a political decision, a very big mistake and a predictable mistake. It’s clear to me the limits of tolerance of the EU public over migration have been reached and it’s understandable if they see this is just the start of the potential movement of hundreds of millions of people.

Those two things together are toxic. They contribute to the rise in populist parties with simplistic solutions, they ruthlessly undermine the EU’s own ideals and what’s happening in the UK is only a precursor to the difficulty they’ve got. But that having been said, it’s much too early to write the EU off. It’s noteworthy that even the countries with populist governments aren’t talking about leaving the EU. On the contrary, they appreciate that the single market and the advantage of what the EU has created are beneficial if they can solve some of the other issues. The question is, will the EU be able to solve those issues? That is the big issue.

From my view as a remainer, the tragedy is this was a great opportunity for the UK to influence the future of the EU, but because we’re leaving we now have no influence. We are therefore going to be an attached spectator to an unfolding political crisis and period of change over which we have no ability to influence but one which we will be affected by.

From Magic Circle to the High Court

Edward Murray, 60, co-founded Allen & Overy (A&O)’s derivatives practice in 1991 while still a senior associate and was until 2013 the senior partner in its derivatives and structured finance group. On 1 October, The Honourable Mr Justice Murray became one of only three solicitors in history to be appointed directly from private practice as a High Court judge. He will sit in the Queen’s Bench Division. We sat down with the City veteran to talk about an unusual journey.

Brexit: Deal or No Deal

Since late August 2018, against a backdrop of growing concern over the prospects for the Brexit negotiations as the clock ticks down, the UK has published batches of ‘Technical Notices’1 on the steps it is taking, and what steps organisations and individuals should consider taking, to prepare for the possibility of a ‘no deal’ Brexit. This article assesses the risk of ‘no deal’, when it will be clear whether it will materialise and what steps companies should consider taking to prepare. Continue reading “Brexit: Deal or No Deal”

Taking the gloves off

The penultimate session of the 2018 Commercial Litigation Summit drew a large audience to hear the views of the most important players in a major dispute – GCs and senior in-house counsel. This debate featured a panel of two private practice litigators – Jenner & Block’s Jason Yardley and Simon Bushell from Signature Litigation, and two senior in-house counsel – Matthew Hibbert of Sky and Tarun Tawakley of Deliveroo. In the middle was a barrister, moderating – Richard Lissack QC of Fountain Court – and a PR veteran, Tim Maltin. Continue reading “Taking the gloves off”

Workplace law: Doyle Clayton

UK Immigration – Rumsfeld déjà vu

Known knowns, known unknowns, unknown unknowns and…

There are few UK organisations where EU citizens living in this country are not clients or customers or, more importantly, employees. Throughout the private and public sectors – from chief executives through to middle management and minimum wage workers, EU citizens have been a cornerstone. Without them – the economic recovery, our attraction to foreign businesses and, of course, investors and entrepreneurs would all have been weakened. Continue reading “Workplace law: Doyle Clayton”

The GC disrupted: eight trends redefining the role

We have long heard about the expectation that general counsel need to be more like business leaders rather than just lawyers. But while in-house counsel may have once viewed this evolution as aspirational or optional, the proliferation of technology and the pace of business today have made it mandatory.

The GC role requires a plethora of skills – giving legal advice is just one of them. Today, GCs must be ready to put on any number of hats, sometimes simultaneously, depending on the situation. Among them: crisis counsellor, risk manager, CEO confidante, board counsellor, and department leader. At the same time, many GCs are being asked to take on these new responsibilities with fewer resources or professional leadership development.

As advisers to clients on their most strategic and transformational transactions, cases and risk management, Morrison & Foerster has witnessed the evolution of the GC role close up. Bringing together insights from our work around the world, along with our market research, we have identified eight trends demonstrating this change. From the perspective of the GC, this could either seem to be daunting or an exciting opportunity to be a significant force in shaping the future of your business.

1. The new GC-CEO relationship

Once upon a time, many CEOs consulted with their GCs only sporadically, and when they did, the discussions were limited to legal matters. The relationship between the two executives was sometimes so distant that they sat on different floors. At most companies, those days are long gone. Today, the predominant CEO-GC relationship is a dynamic and close partnership, involving constant engagement around a wide range of issues.

We have witnessed this new model flourish with the fast-paced growth of technology companies. Because many nascent technology companies were relatively small and had limited resources, hiring someone to serve just as a legal adviser was a luxury few could afford. CEOs knew they needed business-savvy GCs who could take on a broad portfolio of responsibility. That’s still true today of early-stage firms that may be cash-strapped. As two GCs observed in a 2016 Harvard Business Review article: ‘To justify her presence among the first dozen employees, a lawyer must add something beyond legal knowledge to the equation.’ This view is reinforced by Emma McFerran, SVP of legal at Lyst, a disruptor in the fashion retail industry, commenting that: ‘As we have grown so quickly, the value in my relationship with our CEO is that I can be a sounding board on a whole range of business issues and opportunities, whether legal or otherwise. That level of trust is something I value immensely.’

As the speed and complexity of business have increased, this model is prevalent beyond the technology sector. GCs are regularly consulting not only with their CEOs but with leaders from a wide range of business functions. ‘Regulatory compliance such as GDPR can give GCs the opportunity to offer risk-based solutions and engage in meaningful ways with, not only CEOs, but also others in the C-Suite such as CIOs,’ says Annabel Gillham, data privacy specialist at Morrison & Foerster. ‘The most successful GCs have learned to cultivate these relationships, seeing them as opportunities to add value.’

2. The leadership imperative

The psychology professor Carol Dweck popularised the term ‘growth mindset’ to describe a belief that our abilities are not fixed and that we can always learn and improve. More than ever, this attitude is required of GCs who are being asked to take on more responsibilities and acquire new skills. It is a given that GCs have the technical legal capabilities required of the role. But it is the intangible skills and characteristics that are increasingly in demand, and these are different from those required of the role just five to ten years ago. GCs need to be dynamic, inspirational, hungry, influential, and eager to drive change in fast-moving environments. They need to be leaders who can build mixed teams by embracing diversity and nurturing future leaders. For Katherine Bellau, deputy GC at Moneysupermarket Group, this starts with being clear on her personal purpose. ‘Understanding your purpose and how it aligns with the goals of your business enables you to lead with clarity and focus.’

The good news is that these emerging leadership qualities are already present in many GCs. A 2017 study by the executive search firm Heidrick & Struggles assessed how GCs around the world stack up against other executives in eight leadership signatures: harmoniser, forecaster, pilot, collaborator, energiser, provider, producer, and composer. GCs outpaced all other non-CEO C-level executives in the harmoniser (reliable, creates positive and stable environments) and forecaster (learning-oriented, deeply knowledgeable) signatures. But the study also cautioned that in the pilot style, which includes the ability to be comfortable with ambiguity, GCs scored more than 15% lower on average than CEOs and other C-level executives. The bottom line: there is always room to grow.

3. The legal technology revolution

It is hard to overestimate the profound impact that technology has had on the legal industry in the last few years. What’s more, this transformation has only just begun. From billing to contracts to compliance and litigation strategy, technology is constantly inserting itself in the workflow of lawyers in new ways. It is no surprise that a 2017 survey by Thomson Reuters of more than 200 in-house counsel indicated that innovative service delivery through technology was a more critical factor for choosing outside counsel than personal relationships. Additionally, 63% of respondents to a 2018 survey from Right Hat and ELD International of more than 100 legal services buyers said that implementing technological tools/systems for efficiency and performance was their team’s primary objective beyond delivering legal advice.

But while legal technology offers so much promise – savings, efficiency, speed, new insights, etc – the prospect of keeping up can be overwhelming. Knowing how best to exploit all of these opportunities requires a network and available budget. For GCs, that means getting comfortable with collaborating with outside partners. The fact is, knowledge in this space is diffuse. Even at the most sophisticated companies, the best ideas will reside with external sources.

In our experience, the best outcomes around innovation have been the result of close collaboration with clients. ‘Every client has different needs,’ says Alistair Maughan, technology partner at Morrison & Foerster. ‘With technology, it’s important to experiment with solutions. There is no one size that fits all.’

4. The urgency bias

When confronted with either completing urgent tasks within a limited time window or working on important matters with no definite deadlines, many of us will choose the former. That is confirmed in findings recently published in the Journal of Consumer Research. Perhaps more than any C-suite executives, GCs need to be aware of this tendency to favour the urgent over the important.

In any given day, there is a constant stream of urgent matters to tend to – and those can quickly swallow a GC’s mental energy. But it is critical to recognise the need to put time aside for what’s truly important, not just what is urgent. Defining what is truly important, however, must be re-evaluated from time to time – which will likely require a realignment of resources. In Morrison & Foerster’s General Counsel Up-At-Night Report that surveyed more than 200 GC and other in-house counsel, we discovered a significant gap between the commercial importance that in-house counsel assigned to things like privacy and data security and the amount of time their departments devoted to them. It is easy for GCs to become overwhelmed with so much on their plate. But the best GCs learn to keep an eye on the horizon. Michael Cunningham, GC for the open-source solutions firm Red Hat, told Modern Counsel that he regularly reserves time to plan for the future and encourages his colleagues to do the same.

5. Increased exposure to crises

There may be no better test of a GC’s value and mettle than his or her handling of a crisis. When others are losing their cool, a GC can be a calming influence. Conversely, when a crisis is not being taken seriously enough internally, a GC can convey the required urgency needed.

If a GC has not yet been tested by a crisis, it is likely to be only a matter of time. We can thank, in large part, technology for this development, which has exposed companies to a range of new calamities, with data breaches being among the most common. The explosion of social media, which can act as an accelerant to a crisis, has increased the stakes for responding quickly and appropriately.

These factors help explain why 63% of those surveyed in our General Counsel Up-at-Night Report responded that risk and crisis management were essential challenges for their legal department. In the same survey, risks to a company’s brand and market reputation were cited most frequently as top concerns.

Of course, the best antidote to these concerns is preparation, and that is where GCs can take the lead.

‘Too many companies are woefully underprepared for a crisis,’ says Gemma Anderson, litigation and crisis management partner at Morrison & Foerster. ‘While every crisis is different, many of them have a lot of factors in common. Smart GCs recognise this and are preparing for what can be anticipated, lining

up stakeholders and processes so that they can respond in a measured and strategic way.’

6. The rise of the chief risk officer

Just two decades ago, the chief risk officer (CRO) was a new position mostly found in the financial and insurance sectors. But with the ever-increasing complexity and risks facing companies from globalisation, technology, and increased regulation, the position has been introduced across a range of industries.

The rise of the CRO should be welcome news to legal heads. The CRO takes a broader view of risk than just one domain like legal, and often reports to the CEO or CFO. Although the job was once viewed as just saying no to prevent losses, it has evolved into a more proactive role in which risks can be exploited for gain. Together, GCs and CROs can form a powerful team that unites behind a shared goal of risk agility and growth. This allows the GC to be a more effective business leader focused on commercial growth.

7. The globalisation of business

Just as GCs are being asked to adopt a wider perspective through which to see their roles, they are also being required to manage matters beyond markets and jurisdictions in their home countries. Understanding how to navigate new political and legal terrain is an absolute requirement and expected competency of GCs.

Take the rapid rise of cross-border M&A. Although cross-border deal activity declined 10% last year, according to Thomson Reuters, it will continue to be a key driver of future transactions. As recently noted by Mergermarket, despite political uncertainty in specific regions, many companies see more upside in spreading risk over various markets rather than consolidating positions at home.

The demand for technology assets will also likely continue to drive cross-border transactions. ‘It seems like no matter the industry, companies are on the hunt for technology assets that will help them better compete,’ says Dan Coppel, an M&A partner in Morrison & Foerster’s corporate group. ‘To get the best deal possible, it’s important that companies do their homework on the local market.’

8. The data drive behind decision-making

Just about every major strategic corporate decision begins with data. And increasingly many start and end with data. With the development of artificial intelligence, there is no sign of data-driven decisions abating.

If GCs want to maintain credibility with management, they must embrace data, especially when it comes to law firm relationships. A survey of more than 300 GCs located in Europe, North America, and the Asia-Pacific region, conducted by The Lawyer and Globality, lamented the lack of tools and data available to help them evaluate firms.

But some GCs are getting creative. Last summer, GCs from 25 major companies announced that they had teamed up to share data about their law firms, including billing rates, practice areas, and other business information. Their aim, they suggested in an open letter, was to foster a constructive dialogue with law firm leaders about how best to collaborate.

‘We believe that, working together, we can provide a helpful road map, suggesting which practices and innovations lead to positive results and strong relationships,’ they wrote.

‘Through better information, we hope to move the profession forward.’

The role of the GC is changing rapidly!

We are fortunate to work with some of the most talented GCs around the world. They come from diverse backgrounds, bring different skills to their roles, and work for companies of all sizes. But the great ones all share at least one crucial trait: an enthusiasm for the opportunity to play a role in growing their businesses and developing teams.

Some seem born with this attitude, but we’ve seen others cultivate it and inspire their colleagues. These GCs have tossed aside old ideas to meet the new demands of today and tomorrow. They relish the idea of playing a leading role in their company’s history and to leave a legacy.

So when you look back, will you have been a safe (commercially-minded) pair of hands; someone who’s risk aware but not risk averse; or a leader who is in tune with yourself, your business and our changing world?

Morrison & Foerster acts at the intersection of law, business, and technology, supporting GCs as leaders around the world delivering value to their organisations and teams. This article is based on our observations, insights, and work with clients and market research.

Howden on M&A insurance

Recent years have seen global shifts in both policy frameworks for screening inward foreign direct investment (FDI) and the way in which those frameworks are applied. The result is a more uncertain environment for foreign investment, which parties to a transaction will have to consider how to navigate earlier in the transaction process.

1. What is W&I Insurance?

As the name suggests, W&I insurance provides financial cover to the insured in the event of a breach of warranty or a claim under a tax indemnity.

The W&I policy can be held by either the seller or the buyer. While it is much more common for W&I insurance to be placed on the buy-side, it is often the seller that introduces the idea of insurance to the deal. The advantage of insuring the buyer (rather than the seller) is that it allows a direct claim to be made against the insurer, avoiding the need to pursue the seller. In turn, this allows the seller to cap its liability at a low level under the SPA (typically between 0-1% of the enterprise value of the target business).

2. Why is W&I insurance gaining traction on corporate transactions?

The use of W&I insurance can have benefits for both buyers and sellers.

On the sell-side, W&I insurance allows sellers to ensure clean exits. In the corporate setting, the product is frequently used in the context of carve outs or sales of distinct business units, especially when the funds from such divestitures are required elsewhere in a group. In such situations, it is not uncommon to find that the sellers do not have day-to-day knowledge about the target – and therefore, feel uncomfortable giving the warranties. Conversely, management who have dealt with the day-to-day affairs of the business often do not have equity and are, therefore, unwilling to stand behind the warranties. As such, W&I Insurance can be used to great effect to bridge this gap and give either the seller or the management team the comfort required to provide the warranties – either by permitting them to cap their liability at a very low level (often at £1) or by enabling them to give warranties on a blanket knowledge-qualified basis. Through the W&I policy, the insurer will disregard the liability cap and provide coverage up to the agreed policy limit. Insurers can also disregard the blanket knowledge qualifier and provide coverage for the warranties on an unqualified basis (subject to an additional premium and comfort that due and careful enquiry has been made of the management team).

On the buy-side, there are three principle benefits for corporates:

- It allows the buyer to claim against an ‘A’-rated insurer. This is of particular importance where the corporate is buying from individuals or funds whose financial covenant is weak.

- When buying from private equity houses, it enables buyers to push for warranty protection where, in the absence of insurance, none would be offered.

- It can give buyers an advantage in a competitive auction, by allowing the buyer to reduce the seller’s liability in their SPA mark-up and thereby make their bid more attractive.

3. How do insurers get comfortable with taking on these risks?

The majority of insurance underwriters are now ex-corporate lawyers or investment bankers who have hands-on experience of running M&A processes. As such, while the underwriters are not experts in the underlying sector/assets, they are able to look at how the parties have conducted the transaction to ensure that a thorough due diligence and disclosure process has been undertaken. The knowledge that a comprehensive diligence process has been carried out is key to providing insurers with the requisite comfort to take on the liabilities under the warranties and the tax indemnity.

As part of their underwriting process, insurers will require access to the virtual data room and, on a non-reliance basis, the due diligence reports that have been prepared for the transaction. At a minimum, insurers will expect there to be legal, financial and tax due diligence. These reports should be in written form and prepared by professional external advisers or, if internally prepared, by people who are highly experienced in their respective field. It is worth noting that insurers will be anxious to see that insurance is not being used as a replacement for thorough due diligence and, as such, it is essential to show that the matters covered under the warranties/tax indemnity are verified, where possible, by the due diligence reports.

4. How much cover is usually purchased and what does it cost?

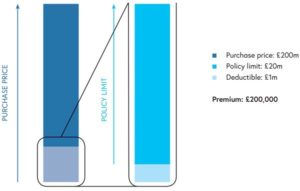

We typically see policy limits in the region of 10–30% of the enterprise value. The premium is expressed as a percentage of the policy limit – this is known as the ‘rate on line’. The premium is a single one-off payment for the entire policy period and is normally due shortly after closing. By way of illustration on a £200m transaction, a 10% policy limit represents £20m of cover. At a ‘rate on line’ of 1% (which is a good rough guide for operational businesses in the UK), this would represent a single premium payment of £200,000.

Insurers will also apply an excess to the policy. Historically this was set at 1% of the enterprise value for European targets. However, increased insurer competition has driven excesses down and it is now common to obtain an excess of 0.5% of the enterprise value.

A de minimis will also apply to each claim under the policy. This typically matches the de minimis applied under the SPA. However, it is important to note that insurers will expect the materiality threshold applied to the due diligence reports to be the same as or lower than the de minimis.

The insurer will set a timeframe within which claims can be made for a breach of warranty or claims under the tax indemnity – this is the policy period. The policy period is normally two years for general warranties, seven years for tax warranties/a tax indemnity and seven years for title and capacity warranties. It is worth noting that these time periods do not need to reflect the commercially agreed position under the SPA.

5. How does cover under the W&I policy differ from the cover provided under the SPA?

While W&I insurance is an incredibly helpful tool for the reasons explained above, it is essential that buyers understand that the cover provided by W&I insurance does not precisely replicate the cover typically provided by a seller under the warranties or a tax indemnity.

W&I insurance is designed to cover unknown risks. As such, any matters fairly disclosed within the due diligence reports, the SPA/disclosure letter or within the virtual data room typically qualify for cover under the policy.

W&I policies also include standard exclusions from cover. The precise list of exclusions varies from insurer to insurer and from transaction to transaction (depending on the sector/nature of the underlying asset). However, as a general rule, the following matters are excluded:

- the non-availability of carried-forward tax assets post policy inception;

- issues actually known to the insured at policy inception;

- matters fairly disclosed within the virtual data room or due diligence reports;

- forward-looking statements;

- leakage/purchase price adjustments;

- secondary tax liabilities;

- transfer pricing;

- physical and structural defects/condition of assets;

- pollution;

- pension underfunding risks; and

- fines and penalties which are uninsurable by law.

In addition to the above, insurers will often attempt to exclude liability for, where relevant, issues such as professional indemnity, product liability and cyber security. The argument here is that the target should have existing policies in place to cover these risks and should not be relying on the W&I policy to provide such protection. However, provided the broker can supply the insurer with the existing policies or evidence that the existing policies are adequate and robust, many insurers can get comfortable with providing cover for these issues (sitting in excess of the limits on the existing policies).

Given the potential limitations mentioned above, we have seen a significant increase in the use of specific risk policies (ie policies covering specific matters identified during a diligence process) over the last year. These policies are particularly prevalent in relation to tax risks identified during the due diligence process.

6. What is specific tax risk insurance?

Specific tax risk insurance provides financial cover to an insured in the event of a successful challenge by a tax authority on a specified tax risk. In addition to the disputed tax, the policy can provide cover for associated interest and penalties, and the external legal costs of the insured incurred as a result of defending a tax authority challenge.

7. When is specific tax risk insurance used?

In the context of M&A transactions, we find the product is typically used either where the quantum of a known tax risk sitting within the target group is of such magnitude that the seller and buyer cannot agree between themselves on an acceptable risk-sharing allocation, and the transfer of the known tax risk to the insurance market is the only way to facilitate the deal, or, where the buyer is seeking to price-chip the seller in respect of a known tax risk and, as an alternative to the price chip, the seller sources an insurance policy for the benefit of the buyer.

Specific tax risk insurance can also be used outside of a transactional context. We are increasingly seeing corporates explore the use of the product as means to hedge tax risk they would otherwise be carrying on balance sheet. As an example we have recently worked with a large corporate to arrange insurance cover for a known tax risk arising from an internal group restructuring.

8. What types of tax risk are insurable and how much does it cost?

Insurers will look to a number of factors when assessing the insurability of a known tax risk including, but not limited to, the nature of the tax risk, the relative strength and legal basis of the tax position taken, the perceived likelihood of an audit into the risk arising and the jurisdiction of the risk.

The outcome of the increasingly commercial approach being taken by tax insurers is that tax risk is now insurable across most European jurisdictions provided that the risk is classified as either low or medium risk (high risk is still typically uninsurable).

Pricing for specific tax risk insurance is very much fact dependent and will vary from risk to risk. The rate on line is typically 2%-6% of the policy limit, depending on the risk.

9. What other M&A insurance products are available?

The creative application of insurance is continuing apace, eradicating the traditional view that insurance is only relevant to a limited selection of clients and situations. There are three insurance products, in particular, that we are seeing increasingly used in the context of M&A transactions: (i) litigation buy-out; (ii) environmental; and (iii) title/legal indemnity insurance.

- Litigation buy-out insurance is used to cover losses arising from a litigation process that a target business is involved in at the time of an acquisition. Insurers will typically only insure ‘low-risk’ litigations, with the policy providing the greatest benefits when buyers and sellers simply cannot agree on how to allocate such risks. A recent example saw the target business in question have historic involvement in a cartel. The target had whistle-blown and gained immunity from the relevant authorities, while the other cartel participants all received fines. These participants clubbed together and sought to challenge the immunity of the whistle-blowing target. The challenge was ongoing during the acquisition process, and on the strength of two legal opinions, Howden was able to structure a policy that saw the buyer indemnified for losses suffered in the event the challenge was successful. Pricing can range from 5-15% of the policy limit, depending on the nature and jurisdiction of the risk.

- Environmental insurance is used to cover both known and unknown pollution events, typically for manufacturing businesses. While W&I insurance will typically cover legal environmental matters (correct permits etc), it often excludes pollution/clean up matters. Environmental insurance is a useful tool to supplement W&I insurance and provide such cover. Pricing ranges from 1-5% of the policy limit.

- Title/legal indemnity insurance is used to cover both known and unknown matters surrounding title to shares or assets. While historically a product primarily used on real estate transactions, we have seen a significant upward shift in the use of the product on operational transactions, in particular where real estate contributes a significant portion of a target business’ value or where the covenant strength of a seller is questioned. The product can also be used to streamline due diligence processes, with title insurers happy to provide cover to share and asset ownership of a group when only a 10-20% sample has been diligenced.

In addition to the above, recent innovation within the insurance market has resulted in the advent of new products, such as break-fee insurance. Break-fee insurance policies are designed to provide protection to a buyer in the event that it becomes liable to pay a break fee to the seller as a result, for example, of a transaction not proceeding to completion because regulatory approval is denied.

We anticipate that the insurance market will show a continued commitment to innovation and that insurance will increasingly provide an efficient way to unlock difficult negotiations and manage risk on M&A transactions.

We anticipate that the insurance market will show a continued commitment to innovation and that insurance will increasingly provide an efficient way to unlock difficult negotiations and manage risk on M&A transactions.

10. Are corporates already using this?

We spoke to the general counsel at Spirax-Sarco Engineering, Andy Robson, on his experiences of using M&A insurance in a corporate deal context and why he believes it is already an essential component of the M&A process.

Spirax‐Sarco Engineering plc comprises two world‐leading businesses, Spirax Sarco for steam and electrical thermal energy solutions and Watson‐Marlow Fluid Technology Group for niche peristaltic pumps and associated fluid path technologies. It is a FTSE250 company (currently on the FTSE100 reserve list) and has experienced high growth over recent years, driven both organically and via a number of strategic acquisitions. The company made three significant acquisitions in 2017, including the Pittsburgh-based thermal technology company Chromalox Inc for $415m and the German-headquartered boiler control systems business, Gestra, for €186m. The company used W&I insurance on both of these transactions.

What are your general thoughts on M&A insurance, having used the product on your recent acquisitions?

In my view it is a must have if an organisation is engaged in international M&A, especially when acquiring good assets from private equity houses. Private equity houses have very little appetite for providing business warranties and this is one way of providing yourself, as a buyer, with an acceptable level of protection. For the mid-sized and larger transactions it is almost seen as a market standard, with the investment banks including a requirement for W&I very early on in the sale processes. It should also be high on the agenda when there is any uncertainty about the covenant strength of a seller.

You’ve used W&I insurance on the buy side, have you considered using it on the sell side?

If you are in-house counsel with a blue chip company and a sale means the company taking on long–term liabilities, I expect boards will be asking why the company is not taking advantage of M&A insurance to curtail these liabilities. It is especially relevant when considering the sale of a distinct business unit, where the seller might have had little day-to-day involvement in the management of the business, and as such will be looking to limit its liability under the SPA.

Do you have any advice for lawyers within in-house legal functions on the use of the products?

I would encourage them to get familiar with the M&A insurance products that are available in the market and begin to integrate them into their transactions from an early stage. It would be a mistake to view M&A insurance as a secondary consideration.

Instead build time into the process to engage with an experienced broker and make the most of the independent review and advice that they can offer.

Herbert Smith Freehills on foreign investment

Recent years have seen global shifts in both policy frameworks for screening inward foreign direct investment (FDI) and the way in which those frameworks are applied. The result is a more uncertain environment for foreign investment, which parties to a transaction will have to consider how to navigate earlier in the transaction process.

An increasing number of transactions are being blocked by governments around the world. Why is that?

Some jurisdictions have always been reluctant to let overseas companies acquire their domestic businesses. However, even in jurisdictions that have traditionally been more open to foreign investment, governments are becoming more interventionist.

This change in more open jurisdictions comes against a backdrop of protectionist political and media forces and, more particularly but not exclusively, concerns about investments by China. The focus of Chinese outbound investment has moved from a focus on natural resources to a broader range of sectors, including critical infrastructure, such as utilities, and high-tech industries. This shift has raised national security concerns in many jurisdictions.

There is also a degree of discontent that companies wishing to move into China are sometimes denied equal rights and it is possible that, by taking action against Chinese companies investing in their home jurisdiction, governments may also be trying to make China reconsider its own policies.

Finally, governmental concerns are not confined to national security but extend to wider issues such as the acquirer’s intentions for the target, including any impact on employment and the economy, as well as any important research and development activities being carried out by the target.

The US is a prime example of a jurisdiction where a number of transactions have recently been blocked. CFIUS (the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States) reviews transactions that could result in control of a US business by a foreign person; its role is to assess the effect of such transactions on the national security of the US and make recommendations to the US president as to enforcement action. We have seen CFIUS intervene in more transactions recently. In line with wider global trends, these have not been confined to transactions which raise traditional national security concerns but include Canyon Bridge’s proposed acquisition of Lattice Semiconductor and Ant Financial’s proposed acquisition of MoneyGram, where the concerns were around access to technology and data.

However, the trend is not confined to the US. For example, in the UK, the government intervened in the acquisition of Sepura by Hytera Communications. Sepura provides the radio devices used by the emergency services in the UK. The government accepted statutory undertakings rather than blocking the transaction entirely; the undertakings given are designed to provide assurance that sensitive information and technology is protected and to ensure UK capability in servicing and maintaining the radio devices. It has also issued an intervention notice in connection with the proposed acquisition of Northern Aerospace by Gardner Aerospace, a subsidiary of Shaanxi Ligeance Mineral Resources.

The Canadian government has also recently blocked the sale of Canadian construction company Aecon Group to Chinese interests, citing national security concerns.

What powers do governments have to intervene?

The power to intervene inevitably varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction but national security is well established as the key justification for public interest intervention. However, as technology evolves, national security is no longer confined to conventional forms of defence but is extending to critical infrastructure and technology.

In the UK, under the Enterprise Act, the government can intervene on the grounds of national security, media plurality/standards and financial stability.

For transactions falling within the jurisdictional scope of the EU Merger Regulation (EUMR), the scope for intervention is limited to protecting public security, media plurality and prudential rules (further interests may be invoked, but only with the consent of the European Commission).

Where a transaction meets the criteria for intervention, rather than blocking an acquisition outright, governments may seek undertakings to address the specific concerns. This was done on the acquisition of Sepura by Hytera (discussed above). The post-offer undertakings regime in the UK Takeover Code has also been used to address political concerns – for example on the takeover of ARM Holdings by SoftBank in 2016, SoftBank undertook to keep the ARM headquarters in the UK and to double the employee headcount in the UK.

It is now relatively commonplace for acquirers to give commitments on a transaction, for example in relation to domestic investment or employment. This was seen when the Italian ship maker Fincantieri took a 51% stake in French shipbuilder STX in 2017. Having initially resisted the transaction, the French government loaned a 1% stake in STX, which gave Fincantieri control of STX. The French government has however retained the option to take back that 1% stake, and therefore control, if Fincantieri fails to meet the commitments it has given, including in relation to the protection of jobs.

In France, acquirers in a wide range of sectors, impacting on the ‘integrity, security, and continuity of supply’ in the energy, water, defence, transport and communications sectors, must consult with the government on their intentions and receive a formal blessing. This obligation to consult seeks to avoid breaching EU law by simply requiring that an acquirer engages and seeks authorisation from the French state on the basis of protecting its legitimate interests and gives the French authorities significant power when it comes to scrutinising a transaction and securing commitments from the parties as part of that process.

In Australia, there have been a number of recent high-profile prohibitions under the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975, such as proposed Chinese investments in a cattle business, S. Kidman and Co, and in an electricity distribution company, Ausgrid.

What steps are being taken to extend governments’ powers to intervene?

We are seeing a range of actions being taken in various countries to extend governments’ power to intervene in transactions that raise national security concerns.

In the UK, the government has lowered the thresholds at which it can intervene for transactions in certain sectors. The sectors that are subject to the new thresholds are: the development or production of items for military, or military and civilian, use; the development and production of quantum technology; and the design and maintenance of aspects of computing hardware.

Transactions generally fall within the jurisdictional scope of the Enterprise Act 2002 where the target’s UK turnover exceeds £70m and/or the transaction will create or enhance a share of supply in the UK of 25% or more. For transactions involving companies in these three sectors, however, the thresholds were lowered, with effect from 11 June 2018, so that the regime applies to transactions in those sectors where the UK turnover exceeds £1m; or one or both of the companies has a 25% or more share of supply of the relevant goods/services in the UK (ie there need not be an increase in the share of supply as a result of the merger).

The UK government has also consulted on more substantive longer-term reforms, including a possible mandatory notification regime and extending the current grounds for national security interventions to a wider category of transactions. The sectors that could fall within this wider regime include civil nuclear, telecommunications, defence, energy and transport. There are no detailed proposals relating to these options at this stage and the government will publish further proposals in due course.

Proposals to expand the CFIUS mandate in the US are also currently under consideration. As in the UK, the balance they are endeavouring to strike is between remaining open to foreign direct investment while protecting against new technologies and risks.

The EU Commission has also unveiled a set of proposals for the screening of foreign direct investments into the EU. The Commission says that, while it recognises the benefits of foreign direct investment and its importance for growth, jobs and innovation in the EU, it also wants to be in a position to take action where foreign investment may affect security or public order. The proposals are set out in a draft Regulation, which establishes a general framework with which any national screening mechanisms of member states will need to comply. The proposed Regulation does not require member states to adopt or maintain a screening mechanism, but aims to ensure that any existing or proposed mechanisms comply with a set of minimum requirements. The Commission will also carry out a detailed analysis of foreign investment flows into the EU and establish a co-ordination group with member states, in order to identify joint strategic concerns and consider possible solutions in the area of foreign direct investment.

There are also reports that Germany’s federal ministry for economic affairs and energy is concerned about Chinese takeovers of German high-tech companies and the resulting effects on employment in Germany. Minister Peter Altmaier is reportedly urging the EU to pass legislation before the end of the year to facilitate the examination of inward foreign direct investment. On a national level, Altmaier has reportedly ordered his ministry to look into whether the government’s right to veto non-welcome investments can be expanded, by tightening regulations that target in particular foreign investments in so-called ‘critical infrastructure’, and lowering the threshold for government intervention from the current 25% of the target’s equity capital to as low as 10%.

In France, the list of covered sectors and technologies in respect of which the government must be consulted is in the process of being expanded to cover artificial intelligence and data storage.

What should parties to a transaction do to address foreign investment controls?

Parties must consider early in a transaction whether it is likely to give rise to foreign investment issues and what the impact of any issues may be.

Given the trend for governments to intervene in a wider range of transactions and on broader grounds, it will not just be the obvious transactions that attract political interest. Acquisitions of businesses involved in critical infrastructure or technologies may raise concerns. As well as acquisitions of whole businesses, acquisitions of minority stakes could also give rise to issues, where those stakes confer a degree of control or influence over the target business.

Parties should establish whether there are mandatory filing or approval requirements (for example to CFIUS) and assess whether to make a notification under any voluntary regime. It can be useful, depending on the jurisdiction(s) involved, to make early contact with the relevant foreign investment authorities to start a dialogue about the purchaser’s rationale for the deal and, if appropriate, plans for the target business. Foreign investment decisions are not always published (CFIUS is the prime example of this) and so the detail of the specific objections that have arisen in previous cases is not always clear.

If there is a possibility that a transaction might give rise to issues, parties should also consider what actions they could take or commitments they could give to mitigate the risk of intervention. These could be structural (eg selling off part of the business acquired) and/or behavioural (these could include protecting the confidentiality of commercially sensitive information, committing to continue with certain research and development programmes, granting the relevant government access rights to assets, etc).

Transactions where extensive rationalisation or consolidation plans are proposed may also be subject to scrutiny – while these sorts of proposals may be attractive to investors, they are likely to cause concern among politicians. Governments may therefore seek commitments from the acquirer to address any concerns that they have.

Parties may also wish to consider measures to allocate FDI risks on a transaction, for example through the use of break fees or reverse break fees or providing that, where jurisdictions carry a high FDI risk, completion in those jurisdictions can be deferred or carved out from the transaction entirely.

It is vital to take a global approach to FDI issues, both in terms of contacts with the relevant investment authorities and positioning the rationale for the transaction with the media. We have seen examples in the past of foreign investment authorities apparently liaising with each other behind the scenes eg in 2016 the German government withdrew its informal approval of the Chinese acquisition (by Fujian Grand Chip) of German semiconductor company Aixtron, apparently after contacts with CFIUS.

We have published an interactive map on foreign investment regulation, from which you can request our country by country guide, which is available here: www.herbertsmithfreehills.com/our-expertise/services/foreign-investment-regulation.

Is this a temporary phase or a more permanent change?

Governments are balancing competing concerns, seeking to remain attractive to foreign investment while scrutinising where the investment is targeted and the terms on which it is made. This follows in part from changes in the global economy as well as the political mood. There is no suggestion that the current level of scrutiny is temporary and that attention will abate with time. In contrast, as technologies become ever more integral to our society and data ever more valuable, the focus on foreign direct investment is likely to stay and more than likely continue to increase.

Dechert Brexit partner

Lawyers in Dechert’s international trade and EU regulation practice bring a unique perspective to the legal and commercial analysis of Brexit, as well as the full range of international trade-related issues. Our combination of experience and global reach enables us to offer a comprehensive mix of legal, strategic and public affairs advice.

In addition to legal expertise, our team draws on experience as former senior policy officials, government regulators, enforcement agents, trade negotiators and public affairs experts in the European Commission and in the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, HM Treasury and the Prime Minister’s Office. The team also calls upon sectoral experts in our network of offices across the US, Europe, Asia and the Middle East.

The team has a practical understanding of how UK and EU institutions operate, how business may be impacted by different policy outcomes and how best to exert influence to achieve the best outcomes for our clients.

Dechert is ‘the go-to firm’ in this space offering ‘cutting-edge and innovative advice’ on Brexit issues – Ranked Tier 1 Risk Advisory: Brexit, The Legal 500 UK 2017.

How Dechert can help

On Brexit: we have already helped industry bodies, companies and governments to plan for the different potential outcomes on 30 March 2019, including in particular:

- rigorous gap and risk analysis: based on an understanding of the likely Brexit options, identifying in detail the issues that a business or industry sector will face, where further research is required and where key risks and opportunities lie;

- planning: advising on practical contingency planning to prepare for potential outcomes and to mitigate key risks;

- priorities and red lines: defining evidence-based objectives that are ambitious while taking account of political realities;

- engagement strategies: developing policy papers and detailed draft treaty language for use with decision-makers in the UK and EU governments and institutions.

We also advise on the full range of legal, regulatory and compliance issues related to international trade including sanctions, export controls, EU regulation, customs and supply chains, international trade law, and anti-bribery, money laundering and corruption.

About Dechert

Dechert is a leading global law firm with 27 offices around the world. We advise on matters and transactions of the greatest complexity, bringing energy, creativity and efficient management of legal issues to deliver commercial and practical advice for clients.

Core EU and Brexit Team

Miriam Gonzalez, co-chair of the firm’s international trade and EU regulation practice, focuses on international and EU trade law policy, with particular experience in WTO and EU internal market regulations. Ms Gonzalez advises clients on Brexit, trade policy, trade agreements, sanctions and embargoes, export controls, antidumping, foreign investment proceedings and EU internal market regulations and infringement proceedings.

Ms Gonzalez previously served as a senior member of the Cabinet for EU External Relations Commissioners, where she had responsibility for trade policy as well as EU relations with the Middle East, the US and Latin America. Ms Gonzalez also acted as lead EU negotiator for the WTO telecoms agreement and led the services negotiations for EU bilateral and WTO accession agreements on e-commerce as well as on energy, postal and construction services.

Ms Gonzalez’s team was awarded ‘Global Trade & Customs Compliance Law Firm of the Year’ at the C5 Women in Compliance Awards. Ms Gonzalez was also recognised as ‘Best in International Trade’ at the European Women in Business Law Awards 2017.

Senior director, London

Email: roger.matthews@dechert.com

Tel: +44 (0)20 7184 7418

Roger Matthews advises on EU law with a particular focus on EU internal market regulation, EU sanctions and trade restrictions and the EU financial services regulatory framework. He advises on both the legal and the practical/procedural aspects of EU law-making, challenging EU legal acts and engaging with EU institutions. He also now assists clients in preparing for Brexit, and developing positions for UK or EU engagement on Brexit negotiations.

Mr Matthews brings a wealth of previous experience on EU law and practice, especially in international trade, sanctions and financial regulation. He has served as a European Commission policy officer on EU sanctions, which included negotiating with EU member states in the EU Council as well as developing the EU’s position on other international trade issues. He has also served as a legal adviser at HM Treasury, advising the UK government on a wide range of EU legal issues.

Email: richard.tauwhare@dechert.com

Tel: +44 (0)20 7184 7350

Richard Tauwhare* advises on all aspects of international and EU trade regulations. He specialises in EU single market and customs union regulations, export licensing, sanctions and trade restrictions, and the trade-related aspects of Brexit.

As a former senior UK diplomat, Richard has represented the UK in EU Council working groups, negotiating on a range of issues related to trade and EU external relations. He has worked in a wide range of diplomatic roles in Africa, Europe, the UN in Geneva and New York, the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe in Paris, and in the Caribbean. He headed Export Control Policy in the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office where he led on strategic export licensing decisions, directed risk assessments, developed UK export controls policy and negotiated international arms control agreements, including the UN Arms Trade Treaty.

*Not engaged in the practice of law.

The rise of risk management

Large businesses today operate in a challenging and uncertain environment. The geopolitical landscape continues to shift in unpredictable ways with, for example, the political, regulatory and economic ramifications of the Brexit vote and the Trump presidency still largely to play out. Stock markets have started to experience jitters following the second-longest bull run in history, while growth in many economies and for many organisations stubbornly refuses to reach pre-financial crisis levels.

Action and reaction

Transformation is occurring across all industries at an accelerating pace, whether driven by technology, transparency or changing customer preferences. Companies operate in a state of almost continual flux: new operating models, turnovers in leadership and new product bets are all more frequent than before. To quote a Google executive, ‘change has never happened this fast before and will never be this slow again’.

This contributes to a complex – and often costly – risk environment for companies to manage. One reaction has been a doubling of the number of assurance functions across the last ten years – such as enterprise risk management, compliance, cyber security, and data privacy teams. Another has been a reduction in risk appetite – research shows more than three quarters of leadership teams have become more risk averse when investing in new projects.

New approaches to risk

This has led to the proliferation of new approaches taken by companies to mitigate risks. New risks, such as those surrounding data breaches and ransomware can now be partly managed, for example through cyber insurance.

Companies are also now looking at ever-present risks, and seeking new ways to mitigate them. For example, recent years have seen the adoption of financial hedging products or insurance in areas like business interruption. Companies also seek more external support to assist with previously internally performed tasks such as supplier due diligence.

Litigation is another longstanding corporate concern, and part of the trend among executives looking to new ways to hedge their risks. More and more large, well-resourced corporates utilise funding to shift some or all of the risk of an adverse outcome in litigation or arbitration.

The personal impact of disputes

The struggle to find sustained growth, ever-increasing business expenses and demands to deliver savings, mean that corporate budgets remain tight. The risks inherent to even the most solid of claims are well understood. While legal fees may be just a fraction of a large company’s total G&A expenses, it is common for those costs to be allocated to an individual business unit or country budget, where the fees can have a significant impact.

For those local business leaders and finance directors, the cash spent pursuing claims may not then be available for other core business-building activities. The impact becomes particularly personal for those who are measured on business performance or variance from a pre-agreed budget or target. Expenses for claims are unpredictable, last for several months or years, and come with no guarantee of a return – and sometimes the exact opposite in the case of an adverse costs award. As such, it’s not surprising that CFOs tell us that lawyers’ fees are often a big topic of conversation at management meetings.

Solutions to manage legal disputes

Litigation funding resolves these problems by offering corporate claimants the opportunity to shift the entirety of this litigation risk on to a third party. It provides comfort to business managers who need to make the internal case to pursue a claim in today’s risk-averse environment, and offers a host of financial and reporting benefits.

For example, when a company funds its own litigation, lawyers’ fees and all other costs associated with pursuing the claim are recognised immediately as an expense. This impacts operating profit for as long as the matter continues, may lower the chance to grow EBITDA if, due to the litigation, money spent on activities such as sales or marketing is reduced, and can reduce the market value of the company by a multiple of those costs.

As third-party funding removes these costs from the balance sheet, increased certainty over legal spending forecasts is obtained, and both the operating profit and valuation of a business may be improved. A business may also find its investors get comfort from the use of funding to shift the company’s litigation risk to a third party.

Other benefits can be seen where a funder is able to provide financing for historic or ongoing operational costs of the business, secured against the proceeds of one or more disputes. In this way a business can use funding for a range of business purposes, whether it is a necessary cash injection, debt refinancing, or simply capital or operational investments in the business.

Future trends

As we look ahead, there are many reasons to believe that the number of disputes involving corporates will increase. Our decades of collective experience at Harbour tell us that economic, geopolitical and regulatory volatility are key drivers of dispute volumes.

The pressure on businesses to move faster than ever before makes it more likely that legal issues will go unnoticed or unaddressed, for example as decision makers fail to involve the legal department early enough in decisions or new initiatives – if at all. Meanwhile new, unpredictable and unfamiliar risks will emanate from investments in new technology and markets.

This will push the pace of adoption of third-party funding by corporates even further, whether in its well-known single-case form or through other innovative products. This steady increase will also continue as knowledge grows among executives of the availability and benefits of funding. Finally, more law firms recognise that funding is a competitive advantage and driver of growth when it forms part of the conversation about fees, even with their well-resourced clients.