It was the football story of the year – eclipsing even Lionel Messi’s move to PSG and football not quite coming home – almost beyond belief in its audacity. On Sunday 18 April, The Times broke a story that 12 leading clubs from England, Spain and Italy had agreed to break away from UEFA’s Champions League competition and launch their own independent format: The European Super League (ESL).

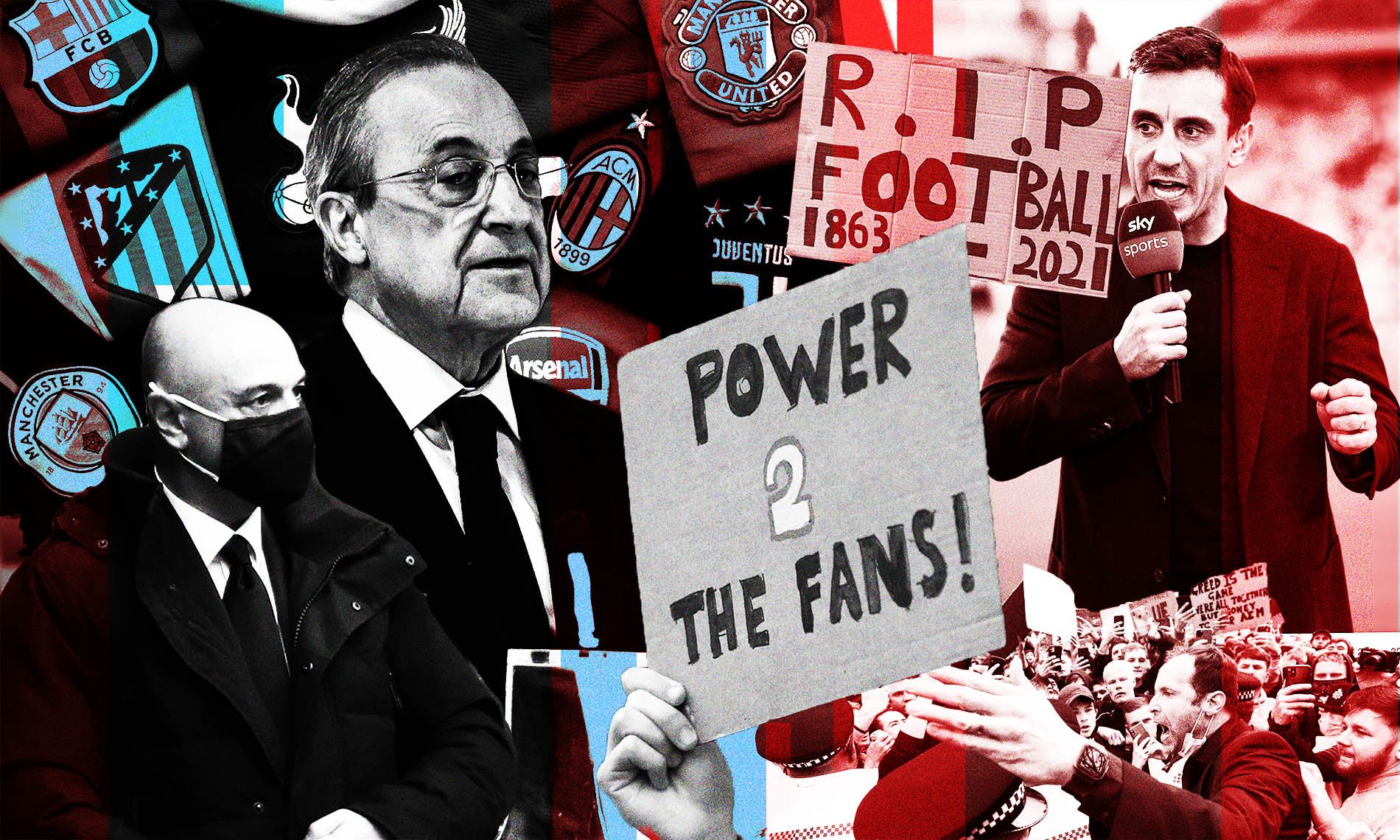

To say the proposals were unpopular is a gross understatement: the following 48 hours of football coverage on all networks was a non-stop barrage of condemnation from fans, players and pundits alike. Former Manchester United captain Gary Neville captured the mood of many when he attacked the 12 clubs live on Sky in a red-faced rant that accused them of arrogance and greed.

Central to the widespread resentment was the ‘closed-shop’ format of the ESL: it featured no promotion or relegation (hallmarks of European football), resembling more of an American-style franchise system, a widely-despised notion among many football fans. Effectively, the 12 clubs (Arsenal, AC Milan, Atlético Madrid, Barcelona, Chelsea, Inter Milan, Juventus, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United, Real Madrid and Tottenham Hotspur) had tried to ring-fence themselves into a 23-year money-making commitment, underpinned by an astonishing pledge by American investment banking giant JPMorgan Chase reportedly worth up to $5bn.

My very first thought was: “Wow, I think they might have just repudiated the contracts of all their players.”

Sean Jones QC, 11KBW

But the ESL plans quickly crumbled under the overwhelming weight of popular outcry, and by the end of that April week, only Real Madrid, Juventus and Barcelona remained committed to the proposals. Boris Johnson had threatened to drop a ‘legislative bomb’ in order to torpedo the plans for the English clubs, and UEFA and global football body FIFA had made similarly substantial threats.

However, from speaking to several legal experts within the industry, in many ways the fallout is only just beginning. As veteran sports barrister Sean Jones QC of 11KBW dryly reflects: ‘Something scared Chelsea, and I don’t think it was fan protests.’

‘Bag of proverbial’

The lawyers’ response to the ESL has broadly matched that of the football world – if anything there is even more disbelief when looking at the proposals through a professional prism. Chelsea fan Jones QC says: ‘My very first thought was: “Wow, I think they might have just repudiated the contracts of all their players.” The individual player contracts have a clause that requires clubs to comply with Premier League rules. But when you look at the Premier League contract, it says you can only enter competitions that it sanctions. Taking competition law to its most basic, the issue is: can clubs organise competitions that they want to? So far as the Premier League and UEFA Rules are concerned, no they can’t and their contracts with their own players also says that they can’t.’

Head of RPC’s commercial division, Jeremy Drew says: ‘My immediate thought was “this is going to go down like a bag of proverbial.” The political pressure will tip it over.’

Jeremy Drew, RPC

Clyde & Co disputes chair Ben Knowles chimes in: ‘When the ESL was announced, I started to think about the sponsors for teams like Leicester City. They have invested considerably in the team in the event of them qualifying for the Champions League – what happens if that suddenly goes away?’

One of the common complaints among supporters was that the whole project had been spearheaded by American owners – particularly John Henry who owns Liverpool, and the Glazer family that has Manchester United – who wanted to replicate the franchise model they were accustomed to. In reality, the ESL was the brainchild of eccentric Real Madrid owner Florentino Pérez. As Graham Shear, Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner partner and head of its sports sector group, observes: ‘This whole project was not started by the US owners, it was started by Pérez. From that perspective there is a degree of deflection in the narrative.’

But that only tells half the story. Fundamentally, the ESL proposals were an act of desperation from a handful of clubs that feared that their financial models had become unsustainable. Emphasising this, Inter Milan and Barcelona (which has recently unveiled debts of over €1bn) have held a fire sale of key assets this summer in a desperate attempt to redress their balance sheets, with Lionel Messi’s landmark switch to PSG and Romelu Lukaku’s transfer to Chelsea among the most notable departures.

Sports law specialist at Sheridans, Daniel Geey, has little sympathy however: ‘It’s their own doing. I don’t mean to say it harshly. A lot of the narrative from the clubs still backing the ESL is the financial model isn’t sustainable. I’m not sure that’s the truth. Their financial model isn’t sustainable, but generally, taking away the financial shock from Covid, the picture was looking a hell of a lot rosier than it has in the past.’

‘We all understood the financial drivers for it,’ says Drew. ‘Some of the clubs appear to be in a terrible mess. Barcelona’s numbers are just unbelievable. But the answer might not just be creating more money, it might just be spending less.’

One senior legal adviser to multiple elite football clubs takes the view that the underlying model is in fact unsustainable and attempts to change it, whether by means of Financial Fair Play regulation or otherwise, are not always well-received. He recalls that when US billionaire Randy Lerner purchased Aston Villa in 2006 he famously imported business principles that were commonplace in American sport, including maintaining control over wages so that they were limited to a percentage of the club’s turnover. When his relationship with then manager Martin O’Neill broke down over how to move the club forward, Lerner described his approach to building the club as ‘aiming always to be as competitive as possible given our size and resources’. That requires a patience and a realism that is a lot less common than it might be. As the lawyer summarises: ‘My experience from advising clubs is that they can be badly run as businesses not least because the owners are often not looking for another business to run. They want an adventure.’

Boris’s bomb

With the dust settling, two opposing legal forces have come rushing into view – potential claims and regulation designed to kill off the ESL for good, and legal action from the remaining ESL aspirants (Juventus, Real Madrid and Barcelona) designed to revive the ailing project.

Boris Johnson did his best to ride a wave of popular outrage as he promised a ‘legislative bomb’ to ensure the ESL would never take place. But it would seem this was more than just typical bluster, as Shear maintains: ‘On the Tuesday morning when clubs started to pull away from the idea, just hours later at 12:48, Boris Johnson made a statement from No. 10. The words “closed shop” were used. That is a clear indicator to the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). If the CMA got involved that would have been the end of it.’

Ben Knowles,

Clyde & Co

Geey takes a more cynical view and plays down the potential CMA probe: ‘The European Basketball League, which I work alongside, has a semi-closed league. And while FIBA, the International Basketball Federation, made a competition claim against that structure, it didn’t really go anywhere. The actual issue about closed or semi-closed is as much a competition law issue as it is an inherent European pyramid structure debate. The European laws are based on the European model of sport – promotion and relegation. I’m not sure that the Commission would want to rule on that. The CMA’s remit would only be applicable for the UK as well. Boris’ threat of a legislative bomb just served the populist wave.’

Drew appeals to basic logic to weigh up the potential threat of competition litigation, referring to the combined wisdom of the law firms representing the 12 clubs, which includes Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, Allen & Overy, Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton and Baker McKenzie (see ‘The official legal team sheets’ below). He argues: ‘On a macro level, if you were JP Morgan and you were the major law firms acting for those clubs, and you had three years of preparation, would you not think you would have been all over (given potential fines) the competition angle? It is reasonable to assume that there were multiple opinions from the major law firms involved that had addressed that point and decided they were OK on it. It is staggering to think JP Morgan, a huge entity, and the law firms involved, signed this off. Can you think of another situation like this where the room was misread so massively? I refuse to believe they expected this popular outcry.’

But the more you scratch the surface, the more the immensely litigious nature of the ESL proposals becomes apparent. Modern football, particularly in Europe, attracts all manner of big-ticket sponsorship deals for companies, and television rights have become a well-publicised bidding war in recent years. This year, the 20 English clubs that make up the Premier League unanimously signed off a renewal of its three-year £5bn television deal with Sky Sports, BT Sport, Amazon Prime Video and BBC Sport.

Knowles attempts to conceptualise the fallout: ‘Rights have been sold up to all sorts of companies like international investors. Those deals are incredibly difficult to put together for the rights holders – terribly difficult to manage. Then if a club moves away from the competition after you’ve bought the rights to a Champions League package, how the hell do you deal with that? That leads to disputes up and down the chain.’

Drew points to the ‘bringing into disrepute’ clause common in most commercial contracts, and how this would have been an area ripe for dispute: ‘If you do something as contentious as this, and if the fans think the sponsor is supporting the breakaway, it’s not great! The only reason we didn’t hear more noise is because the reversal was so swift.’

Next in line would surely be the players themselves – especially after FIFA made a drastic threat to bar any ESL players from appearing in the World Cup. Jones QC illustrates a hypothetical conflict, involving a player at one of the six English clubs that were set to join the ESL: ‘They might think: “It’s a bit inconvenient I’m in this contract, it would be lovely to be a free agent and go elsewhere. This is going to ban me from playing for England, and that’s a repudiatory breach of the trust and confidence duty. By acting in this way you are precluding me from acting in a competition which is vitally important to me.” That’s a strong argument, but an even stronger one is: you’re breaching the Premier League rules and you promised me you wouldn’t. That’s a repudiatory breach.’

Geey confirms that there was an uptick in anxiety from his player clients: ‘The players were taking stock of the implications for them. Different agencies asked how this would play out. If it hadn’t fallen away very quickly, there would have been lots of different dynamics going on. It wasn’t just differences between the clubs and UEFA, it was between clubs and other domestic clubs. There would have been lots of very difficult conversations.’

Going down fighting

Despite the overwhelming popular, political and legal opposition, the remaining ESL adherents are not giving up on their plans without a serious fight. Under the radar of most football fans, the last few months have seen Real Madrid, Barcelona and Juventus challenge UEFA in the Spanish courts, arguing that they have been unfairly restricted by the governing body and that any penalties they receive are illegitimate.

The action was a pre-emptive move by the remaining clubs to avoid recourse from UEFA, FIFA or any other body. Given their perilous financial situations, they are understandably concerned, especially after the six involved Premier League clubs agreed with UEFA in May to a combined £22m goodwill payment to support grassroots football projects.

Clifford Chance has confirmed that it is acting for the ESL on ‘the legal actions initiated vis-à-vis FIFA and UEFA’ as well as other matters, with a legal line-up captained by M&A partner Luis Alonso, finance partner Eduardo García, litigation partner Fernando Irurzun, regulatory partner Jaime Almenar and antitrust partner Miguel Odriozola.

UEFA, on the other hand, is being advised by Ashurst, which has teamed up with Spanish firm MLAB Abogados as co-counsel. MLAB Madrid partner Helmut Brokelmann is leading on the matter for the firm.

And, at the moment, the ESL is succeeding. On Friday 30 July, the remaining clubs celebrated a victory as the 17th Mercantile Court of Madrid ruled that UEFA cannot act against the ESL clubs. In an ominous statement after the ruling, the clubs said: ‘The case will be assessed by the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg, which shall review UEFA’s monopolistic position over European football.’

Drew comments: ‘I’m interested in how fast the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) hears the case. It can take up to 18 months. It will be interesting to see if the EU even wants to deal with it, let alone prioritise it. Or will they delay it? It’s such a hot potato politically. Just imagine if it goes against UEFA?’

But even with legal exoneration, would the ESL be too unpopular to pursue? Drew thinks not: ‘The clubs haven’t given up on it. From a financial standpoint, look at Barcelona. It is in some difficulty. That’s why it hasn’t backtracked yet. That financial tension is not going away – the need for something to change, whether it’s the Champions League being tweaked or something else, the financial pressure is not going to disappear.’

Geey disagrees, quipping: ‘I don’t think those three clubs will just want to play against themselves!’ He adds: ‘In the end, a court decision didn’t cause the majority of the ESL clubs to fall away, it was the court of public opinion. It could just be a PR victory and an opportunity to chase UEFA for loss.’

Daniel Geey, Sheridan

Another card up the ESL group’s sleeve is the contractual obligations that the 12 clubs had signed up to when the plans were made. During the initial uproar, a defiant Pérez had sought to quell any notion of clubs retracting from the ESL, saying in an interview that they were all contractually bound to the plans.

In conjunction with a potential legal justification from the CJEU, where would that leave the situation? Drew says: ‘The thing no-one is commenting on is the risk of claims between those involved. They will have had an agreement, which would have contained provisions. Just imagine if the three clubs that haven’t recanted – if they win that court case and somehow get it back on, would they then bring a claim against the others?’

Knowles is unconvinced: ‘In terms of follow-on litigation – is there too much to lose than gain? The disputes might not happen this time but we are certainly bracing ourselves.’

The backlash

The whole ordeal has left fans hungry for change, and one of the main reactionary points made by the likes of Neville and his Sky Sports colleagues was the plea for a new independent UK football regulator.

To that end, on 19 April the government commissioned the Crouch Review, spearheaded by Conservative MP Tracey Crouch, to establish whether such a watchdog is necessary. In her interim report to culture secretary Oliver Dowden on 22 July, Crouch concluded that a new regulator must be created to preserve the integrity of the beautiful game.

The prospect has been met with a mixed response by lawyers, however. Chiefly, it remains to be seen what kind of powers such a regulator could wield that would bring about meaningful change. Geey outlines his concerns: ‘What will it actually have power over? Licensing agreements, ownership tests? Stakeholder buy-in? There’s all of these soft points that you don’t need an independent regulator to deal with, and then a lot of hard points that get to the heart of football. If you’re going to take that regulatory power away from the FA and others, they’re not going to let go lightly.’

And as Jones QC observes, fans should be careful what they wish for: ‘Having a regulator sounds like a good idea in the abstract, because something bad has happened which we didn’t like. But then you ask: what powers would a regulator have to have to stop this happening? Would they need to have the power to approve which competitions football clubs could enter? If so, where does that lead? In the Chelsea FC museum, the Cross-Channel Cup is there, from the game we played against Le Havre in the ‘90s. I was quite proud of it at the time. Can you really imagine having to apply to a regulator to play in that?’

Drew at least contends that the existence of a new regulator is necessary, before revisiting his more sympathetic appraisal of the modern elite football club: ‘Something should be done. The pubs shut at 11:30 for a reason – it controls the level of drinking you can do, in theory! There’s a degree of regulation we use in society to control things that you might be tempted to abuse. If you’re overspending habitually because it’s a competitive environment, surely there must be some restraints in the rules to preclude it from happening?’

But if a new regulator is not the answer, then what is? There have been muted suggestions that a degree of fan ownership could be the solution, mirroring the widely adopted ‘50+1’ model seen in Germany, whereby most elite clubs are majority owned by fans. This is a less popular alternative however. Knowles simply states: ‘50+1? No fan could afford that in the UK.’ Geey also describes 50+1 as a ‘non-starter’ but acknowledges that it has at least mobilised fans into buying shares as ownership groups: ‘The government isn’t going to start legislating that fans suddenly know more than the owners.’

There is already an interesting fan ownership quirk in the UK, in the form of the Chelsea Pitch Owners (CPO). After suffering severe financial hardship in the 1970s and 1980s, a group of fans created the CPO and bought the freehold to Stamford Bridge and Chelsea FC’s naming rights in 1997 to ensure the club would not fall into the hands of malicious property developers. Jones QC is a member of the CPO, and he is bullish about the fans’ role in protecting the interests of the club: ‘One of the terms of the lease is if they ever leave Stamford Bridge, they have to surrender the name. They have to stop being Chelsea. So if we had gone into the ESL, and Boris dropped his bomb and said “no ESL game could be played in the UK”, that would have had the effect that no games could be played at Stamford Bridge. Some people got very excited about it.’

In fact, the model is so powerful that Jones QC confirmed that Crouch had consulted the CPO as part of her review into the future of football regulation, with a view to adopting it more widely.

In many ways, the ESL fiasco was just the start. One way or another, the world of football is set to be shaken up substantially in the coming years. Even if the breakaway ESL clubs fail in their legal challenge, UEFA’s own Champions League competition is set to undergo a controversial format change that will reserve a ‘legacy’ qualification spot for teams who have performed well historically in the tournament.

And if there is to be a solution to the perennially crazy football business model outside of regulation or fan ownership, why not the ESL? As Drew concludes: ‘Maybe if the plans were handled slowly and more carefully, and the closed-shop aspect was readdressed, it could be back with a vengeance. Depending on your perspective, what a shame they got it wrong!’

The ESL odyssey – A timeline

Sunday 18 April: Around lunchtime, The Times reports that 12 clubs from England, Italy and Spain have agreed to establish a new European Super League (ESL), severing themselves from UEFA’s Champions League competition. Later that day, the clubs are confirmed as AC Milan, Arsenal, Atlético Madrid, Barcelona, Chelsea, Inter Milan, Juventus, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United, Real Madrid and Tottenham Hotspur.

By the afternoon, the Premier League, UEFA, FIFA and even Prime Minister Boris Johnson had robustly condemned the plans.

Just after 11pm BST, the 12 clubs announced that they hoped the ESL would ‘commence as soon as practicable.’

Monday 19 April: Early the next morning, the ESL issued notice of legal proceedings designed to block any potential sanctions from FIFA or UEFA in response to the plans.

That same morning, all 12 clubs then resigned from the European Club Association. Manchester United executive vice-chairman Ed Woodward and Manchester City chief executive Ferran Soriano stood down from their roles at UEFA.

Tuesday 20 April: Late on Monday night, Real Madrid president Florentino Pérez had done an interview on Spanish TV claiming the clubs were contractually bound to the plans. By Tuesday morning, the video had been widely viewed across Europe.

The 14 non-ESL Premier League clubs convened and vowed to ‘consider all actions available’ to prevent the breakaway league from forming.

Before Chelsea’s Tuesday evening game against Brighton at Stamford Bridge, a large group of fans gathered outside the stadium to protest the proposals. Around this time, both Manchester City and Chelsea had hurriedly announced they were looking to pull out of the ESL.

By 10:45pm BST, all six of the English ESL clubs had announced they were withdrawing from the competition.

Wednesday 21 April: Atlético Madrid, AC Milan and Inter Milan also withdrew from the ESL, leaving Juventus, Real Madrid and Barcelona the remaining teams.

In an interview, ESL founder and Juventus chairman Andrea Agnelli conceded that the plans were dead.

The official legal team sheets

AC Milan: Senior legal manager Francesca Muttini, historically advised by White & Case

Arsenal: General counsel Svenja Geissmar, advised by Allen & Overy and Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer

Atlético Madrid: Secretary of the board, Pablo Jiménez de Parga, historically advised by ECIJA.

Barcelona: Director of legal Pere Lluís Mellado, advised by Baker McKenzie

Chelsea: General counsel James Bonington, advised by Allen & Overy and Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer

Inter Milan: Legal counsel manager Cesare Scalia, historically advised by Latham & Watkins and Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton

Juventus: General counsel and chief legal officer Cesare Gabasio, advised by Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton

Liverpool: General counsel Jonathan Bamber, advised by Allen & Overy and Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer

Manchester City: General counsel Simon Cliff, advised by Allen & Overy and Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer

Manchester United: General counsel Patrick Stewart, advised by Allen & Overy and Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer

Real Madrid: Advised by Clifford Chance

Tottenham Hotspur: Head of legal Katie Reed advised by Allen & Overy and Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer

UEFA: Advised by Ashurst and MLAB Abogados

European Super League: Advised by Clifford Chance

JP Morgan: Advised by Latham & Watkins